Part I. Introduction

In a time when the fragility of our planet is more evident than ever, clay offers a medium for reflection and inquiry. Curated by Julia Ellen Lancaster, The Whole World in Our Hands brings together six women sculptors who work with clay to explore themes of ecology, material histories, and human responsibility. Timed to coincide with Earth Overshoot Day, the exhibition challenges viewers to consider the intersections between art, environment, and the fragility of our natural world. Through their work, these artists reveal the material’s capacity to hold time, industrial traces, personal narratives, and the imprints of both natural and human histories, turning it into a space for conversation about our relationship with the earth.

What unites these artists is their engagement with clay’s origins and implications. Some, like Alison Cooke and Rosanna Martin, work with excavated clays sourced from sites shaped by human industry, revealing hidden histories embedded in the landscape. Others, like Julia Ellen Lancaster, embrace a circular practice, treating material as something that is continuously transformed and reused rather than exhausted. Jane Millar engages with the unpredictability of ceramic surfaces, drawing a parallel between chemical transformations and the concealed energies within ourselves. Jacqui Ramrayka explores memory, identity, and cultural displacement through the vessel form. These artists may work differently, but they share a deep commitment to clay, both as a material and as a way to explore and examine how people and nature are connected. Thanks to these artists, clay performs an essential role of bridging past and present, material and maker, and inviting us to reflect.

In The Whole World in Our Hands, clay holds geological history, human activity, and cultural memory. Alison Cooke works with dug clay obtained from construction sites and former industrial landscapes, materials often deemed valueless but rich with hidden histories. Her use of Thames clay, glacial sediment, and industrial waste highlights how extraction and climate cycles have shaped our world.

Julia Ellen Lancaster’s practice emerges from deep engagement with place, collecting clay and other materials from landscapes to form layered compositions. These reflect both physical history and future imagination. Her work creates a conversation between geological history, the present moment, and an imagined future, allowing the material’s history to speak.

In this exhibition, clay also embodies cultural memory and transformation. Jacqui Ramrayka explores themes of identity, loss, and preservation, using porcelain as a metaphor for the Indo-Caribbean diaspora, whose history is marked by migration and reinvention. Her vessels are keepers of forgotten narratives, preserving histories through form and surface.

Rosanna Martin’s work, rooted in childhood memories of playing in a white clay riverbed near an old brickworks, highlights the interplay between industry, place, and material reuse. Her practice embraces sustainability, reclaiming and repurposing clay to encourage curiosity and reflection on consumption and waste.

Jane Millar and Sam Lucas take a more introspective approach, linking materiality to psychological and sensory experiences. Millar’s work explores the relationship between inside and outside and the unseen energy it provides. Her sculptures mask unseen forces within their surfaces, much like the human psyche shields its internal complexities.

Sam Lucas explores the connection between neurodivergence and biodiversity, advocating for the importance of different ways of thinking. She suggests that embracing different ways of thinking could lead to more creative and sustainable solutions for today’s challenges. Shaped by a personal process of meaning-making, her work contributes to the exhibition’s broader theme of fostering connection, understanding, and respect.

Together, these artists engage with clay as a living material that encapsulates time, transformation, and the vulnerability of both human and planetary conditions. The Whole World in Our Hands is not about what we create from clay but how clay reveals the marks we leave on the world. It invites us to think about where materials come from, how industrial processes shape the land, and how artistic practice can serve as a vessel for ecological and philosophical reflection. In this series of interviews, each artist reflects on their relationship with material, landscape, and meaning, offering a personal and collective meditation on the role of clay in shaping the world.

Part II. Interviews with Alison Cooke, Julia Ellen Lancaster, Sam Lucas, Rosanna Martin, Jane Millar, and Jacqui Ramrayka

Interview with Alison Cooke

Why do you work with clay, and how does it connect to ideas about sustainability and shared cultural stories?

I’ve worked with lots of different materials, but clay has versatility, which is something else. I’m very indecisive, and clay suits my lack of commitment/confidence in an idea. If it’s not right, I can lob a bit off, roll it up, or soak it and start from scratch. Until it’s fired, I can change my mind.

I’m interested in where the materials I work with come from and the layers of history and future of that location feed into the work that I make. By working with location-specific materials, there is already a narrative; sometimes, it is so strong just the material itself is enough for me, and I display it as it is.

Because I use dug clay or obtain it from construction sites/mines/scientists, etc., it doesn’t add as much to my carbon footprint as buying commercial clay would. But there is no getting away from firing, being an energy eater, which I’m very aware of, and I always question why I’m firing something.

Another reason I work with clay is that it has no value; it’s mud, it’s everywhere, it’s free. In 2017, I got five tonnes of clay spoil excavated from below the Thames while constructing London’s supersewer. It had negative value, the construction company paid huge amounts to have it removed and placed somewhere else. I like working with something that is valueless.

All cities that sit on clay beds will eventually invest in a clay processing plant, sell local clay, produce local ceramics, and connect the inhabitants to the Earth beneath their feet.

How do the physical properties of the clay from specific sites influence the form, texture, or conceptual direction of your pieces?

The materials I get are unknown and dictate the making process, as often there are very few clay particles (I’m laughing as it’s really not a sensible way to work). I don’t like to add other materials and I sieve out as little as possible. So, grand plans to hand-build some beautiful 3d monster might end up as tiles. It’s limiting, but all the negatives are overridden by my interest in the provenance of the material.

I’m currently working with Jurassic materials, some removed from dinosaur fossils by paleontologists, and the contents of a dinosaur footprint I dug last year. I love what the materials are but they are really tricky. This is what I hope to be showing at Stephen Lawrence Gallery.

In your view, what role does the material memory of clay—its geological and cultural histories—play in addressing contemporary ecological challenges?

To me, the location of a clay (or any material) holds layers of memory/history from that site. Not in a spooky way, just it can make those histories more tangible.

I’ve worked quite a lot with glacial clay dug from eroding cliffs of Norfolk, UK. I like the circular narrative of the movement of material dependent on global temperature. For me, using glacial clay is like a code for climate change as it encapsulates previous global warmings.

This is probably too much info, but… 450k years ago, the North Sea was frozen in a vast glacier that covered Britain as far south as Norfolk; as the global temperature warmed, the edges melted, and the debris held within the glacier was released and formed a moraine. I dig from the terminal moraine, the Cromer Ridge, which has the furthest reach of the glacier.

We are on the same warming trajectory, just sped up by pumping CO2 and methane into the atmosphere. Now that same cliff/moraine is eroding because of sea level rise, and those same particles are being washed out again as the cliff collapses. I like to capture the material at this point in time, save it from the sea, remove it from the circle and use it to make work that references the current climate crisis.

What role do you believe contemporary ceramics can play in fostering global awareness of environmental issues?

Sadly, I doubt those who have the power to reduce our environmental impact in any meaningful way give a hoot about a sustainable future, let alone pottery. But individually, I think people working with clay are physically/psychically more connected to the Earth because they hold, mold, and control it. I like to think that people who buy ceramics/are interested in ceramics, in turn, also feel more connected to the Earth and, with that, consider their personal impact on it.

Interview with Julia Ellen Lancaster

Can you elaborate on how the geology of a place influences the narratives and forms of your sculptures?

The geology of a place is embedded in the narratives and forms of my ceramic sculptures, shaping them in ways that are both intentional and subconscious. When I think about where I’m sourcing clay, I am tapping into the layers of history embedded in the land itself—its past and present converging in my hands. The composition of the clay, shaped by millennia of geological processes, holds the memory of its origins, whether from a riverbed, an eroded cliffside, or an industrial excavation site. I can’t help but be influenced by the architecture, the landscape, the environment, and the flora and fauna surrounding me. These elements seep into a visual language, subtly altering the way I form and shape the sculptures. It becomes a way of excavating not just the physical properties of the material but also the histories, energies, and stories embedded within it.

In some ways, the process extends the notion of Automatism associated with the Surrealist tradition, turning it into a tactile and material-driven experience. As I collect, re-use, and reshape fragments of clay, I allow instinct to guide the process, letting unconscious associations emerge through form and texture. Automatism, for me, is not just about spontaneous mark-making but about channeling the past, realizing imagined histories and futures through the very materiality of clay. The geological origin of materials can act as both a foundation and a catalyst for these transformations—offering a tangible link between time, place, and artistic intuition. In this way, the work becomes a dialogue between deep time, present touch and future imagination, where clay, shaped by the earth, continues to evolve through human hands.

In what ways do your sculptures highlight or reflect the connection between landscapes and human bodies?

For me, landscape and the human body are inextricably linked. We exist because we come from the earth, and over billions of years, this connection has only deepened, becoming more urgent. My ceramic sculptures explore this relationship, using clay—a material that has recorded our history, from a 3,000 BC clay writing tablet to heat-shielding ceramics in space shuttles (Matina Margetts, Clay Conversations, 2024). Working with clay reveals its transformative power; its shape-shifting quality echoes the shifting contours of both land and flesh. Just as landscapes bear the traces of time, erosion, and movement, so too do our bodies, making clay the perfect medium to encapsulate this shared evolution. Its dust lingers, acting as a reminder of our origins and the fleeting nature of existence.

How does your circular, waste-free approach to materials reflect your views on sustainability and our relationship with the natural world?

I’ve always held an overwhelming dislike for waste of any kind; it was ingrained in me from a young age. As a youngster with three siblings, there was no possibility of excess. My Mother, as a single parent before remarrying, was frugal and didn’t indulge our fantasies of new things, in any form. If I wanted something, I had to make it myself from scratch, but that suited me and made me feel good with my hands. Time spent in Tokyo some years ago meant I learnt to ‘make’ with very little, and spending time looking more closely at notions of mending, from ceramics to textiles, had a major impact on my practice. It was here that I discovered the concept of ‘mottanai’, meaning ‘no waste’. In Japan, concepts of care, attention and detail are much more prevalent and inform not only a practice but a way of life.

I find it quite difficult to throw anything away in my studio. Equally, I find it difficult to buy new materials. Instead, I recycle the unwanted materials of other makers. I’ve also learnt to be a little less hard on myself – accepting that sometimes to explore new ideas you do need the ease of a ready-made material. I think a lot about sustainability, and I’m particularly interested in ideas around a ‘soft world’ whereby we’re not stuck on a track of how things have occurred before, finding ways to continually exhaust the earth but instead finding ways to coexist with it, respond to it and accept it has a greater power than us as humans.

What is the significance of incorporating other materials and elements from previously rejected or fired pieces into new works?

Re-using pieces and giving them new life is a way of continuing a form of circular practice. Equally, using minerals and rocks, the make-up of which have been altered or calcinated through extreme heat, signify a multiplicity of surfaces that cannot be replicated exactly. In this way I’m extending the surrendering of control of the materials. There is also an element of the ephemeral that explores ideas of transformation and impermanence, allowing points of reference to sustainability and the preservation of fragile ecosystems. Each element I incorporate already has its own history, pre-existing, forming layers and layers of meaning.

What personal or collective stories emerge from your exploration of a location’s geology and its connection to the community?

I rarely create a piece of work without thinking about the space in which it’s made or shown. I like form and I enjoy the process of physically dealing with it. I’m not a geologist, but I felt most at ease from a young age when I had my hands in dirt. It’s interesting to note that there is a gender bias relating to this act. As a youngster, I desperately wanted to be a boy because, as a girl, I was frowned upon for ‘getting dirty’. That rebellious quality, as well as this gender association, is something I relate to my practice now and the way I work with ceramics. My background is in Fine Art. I had no training in ceramics, but when I started to work with clay, it was obvious that I was going to work with it in such a way that reflected my own experiences.

I am conceptually and emotively exploring my position in the world through material and it’s important for me to remember the reason I initially started making work as being something inside that I felt, and that if I could manifest it in some way, I would understand more about myself and how I coexist with the rest of society. But it needed to be outward looking, not a story about me as an individual needing to fit in.

I’ve always been interested in Architecture and its relationship to the landscape. The forms I make often reflect an idea of future habitation connected to the accumulation of debris. When I was working in Anchor Studio, Newlyn, Cornwall, this was highly evident in that not only did I spend a great deal of time working directly in the landscape, collecting materials that related to the coastline and the structures along the coastline; clay, rust, metal, wood, rocks, shells, but that I then translated these materials into small forms and projects that reflected the architecture of the Anchor studio itself with its own history as an artists’ studio that founded the school of ‘plein air’ painting back in the late 1800’s. In this particular setting, there was already a profound connection with the local community, which, with the support of the Penlee House and Gallery Museum, I was able to connect with. The very tangible outcome being people from the local community who visited the studio often, sometimes bringing me lumps of clay from their own allotments. It was a way of having conversations with those people I wouldn’t have necessarily had and learning about Cornwall as ‘Clay Country.’

How do you envision your work contributing to the conversation about our role in responding to the climate emergency?

My work attempts to merge human endeavor, creative interpretation, and to some extent scientific awareness. Through material choices, process-driven experimentation, and conceptual thinking, I might foster a sense of urgency whilst also offering space for imagination and reflection.

Working with clay is a deeply human act—one that connects us to ancient traditions of making while reflecting our current relationship with the environment. The physicality of shaping, firing, and transforming raw earth into lasting or even temporary forms mirrors the tension between human progress and ecological fragility. By incorporating elements like cracked surfaces, layered textures, and unstable structures, I highlight the precarious balance between destruction and renewal, allowing the viewer to consider their own response to these issues.

My sculptures engage with imagined landscapes and speculative futures and could be seen as exploring what the world might look like if we fail (or succeed) in responding to environmental degradation. Some works reference fossilized remains of extinct species, suggesting a future where what’s familiar to us now exists only as memory. Others take inspiration from regenerative forms—mimicking coral reefs, fungal networks, or bio-adaptive architecture—to propose a world where nature and human structures coexist harmoniously. Through these visual narratives, I’m inviting audiences to question their assumptions and engage emotionally with the urgency of climate change, societal change and injustices.

Detail is central to my work, mirroring the complexity of environmental systems. I may use intricate surface treatments—such as cracked glazes resembling dried riverbeds or erosion, embedded organic materials that burn away in firing, or delicate, structures that seem to teeter on collapse—to evoke both the beauty and fragility of our planet.

What role do you believe contemporary ceramics can play in fostering global awareness of environmental issues?

I think it can only be part of a wider conversation, but in an era of increasing ecological crisis, contemporary ceramics can serve as a powerful medium for raising awareness about environmental issues. As a material intrinsically tied to the earth, clay embodies the history, fragility, and resilience of our planet. Ceramic artists engage with these themes by exploring sustainable practices, using local or reclaimed materials, and addressing pressing concerns such as climate change, resource depletion, and habitat destruction. Through their work, they create objects that not only communicate these issues but also encourage a deeper connection between audiences and the natural world.

One of the most compelling aspects of ceramics is its ability to bridge past and present, offering a material lineage that underscores the long-term consequences of human impact on the environment. Artists experimenting with raw, unprocessed clay, for example, highlight the geological and cultural histories embedded in the material, reminding us of the landscapes that are rapidly disappearing due to industrialization. Others use alternative firing techniques or biodegradable glazes to reduce the carbon footprint of their practice as an example of more sustainable approaches in the art world. In addition, conceptual ceramic works often depict themes of erosion, pollution, or extinction, making visible the slow but devastating changes occurring in ecosystems worldwide.

Ceramics as a tactile and enduring medium invite reflection on the value of handmade, durable objects in contrast to mass production and consumer waste. In a society dominated by disposability, ceramic art encourages a shift toward longevity and mindfulness—values that are essential in combating environmental degradation. By engaging communities through exhibitions, workshops, and public installations, ceramic artists foster dialogue on sustainability and advocate for a more responsible relationship with the earth.

I think contemporary ceramics play a crucial role in environmental awareness by merging materiality, history, and artistic expression. Through sustainable practices, conceptual storytelling, and community engagement, ceramic artists can therefore reconsider our impact on the planet and inspire action toward a more ecologically conscious future. Community-based projects, such as Future Artefacts by British artist Tessa Eastman, engage audiences in conversations about climate change by inviting them to create ceramic objects inspired by imagined post-apocalyptic landscapes. Public installations, like those of Magdalene Odundo, which draw from indigenous ceramic traditions to emphasize sustainable craftsmanship, further encourage a reconnection with ecological consciousness through traditional knowledge and techniques.

I was asked recently about the element of ‘risk’ in my work, and I blabbered on about the process itself, materiality and the need for experimentation. A few days later, I read this quote by David Bowie which just really resonated with me;

‘Always go a little bit further into the water than you feel you’re capable of, go a little bit out of your depth, and when you don’t feel your feet are quite touching the bottom, you’re just about in the right place’ – David Bowie

Interview with Sam Lucas

What inspired you to explore the experience of feeling disconnected or uncomfortable (in relation to the body), and how does clay help you express these emotions?

My father’s little brother Michael had cerebral palsy, along with other differences, which was my first realisation that people’s own bodies don’t always do what they want them to, which was in the 1970’s and it was a particularly difficult time to be disabled as there was a lot of stigma about it and people weren’t always kind.

As children, we are free to spin and swirl as the world appears to revolve around us, if we are lucky. We develop our identity and perception of ourselves, over time, within the world through our senses and experiences. Our bodies are oblivious to the turbulence that lies ahead that will leave the traces of the journey like the rings of a tree or the lines on a map. We are born embodied, with a fully developed unconscious understanding of the world within.

On this journey, we are taught the social constructs of how to navigate this ship that is our body, through this disembodied process. The separated navigator that is our mind may lose its bearings and hit the rocks, leaving scars that may not easily heal. We are simultaneously becoming and forgetting this embodied diversity. For some, this is not straightforward. Some of the people who experience sensory differences may continue living in this world of spinning in their circle, with a complex connection to the outside world.

As a child, I was spinning around in my own world and felt as though something was different. I didn’t seem to be able to engage in the same way that others did. I felt like a tourist looking in from the outside and experienced a sense of displacement within my own skin. I come from a neurodiverse family, and when I was in my early teens, I remember turning to my brother and saying; ‘It’s different for girls”. We know it’s exhausting but we find it easier to hide our differences, we can assimilate and be shapeshifters.

It sounds like a cliché, but it was clays malleability that I was drawn to and during my troubled teens, I was offered the ceramics room at school. I guess it was inevitable as I grew up in the country on the edge of a town, playing in the streams, building dams and scrabbling about in the mud and clay. I was literally away with the fairies.

I feel as though the clay spoke to me. It called to me and gave me a sanctuary from the social confusion. I struggle with words and through this dance with clay I can create narrative objects. These artefacts may be ambiguous to others but are a process of meaning making for me.

How does your background in creative arts and your experience with young people with complex needs influence your approach to ceramics?

My creating in clay began long before I began working alongside others. I had many jobs and travelled, spending months abroad. I had grown up with an amazing, strong and inspirational single mother, necessity meant we moved a lot. My hyperactivity made it impossible for me, I struggled to settle, to tolerate the regimented school structure and expectations, and this resulted in me being a truant from The Grammar School it was suspected I had ‘School phobia’.

Working in the creative arts department alongside some amazing people has given me a sense of safety and structure that was lacking in my previous life and ironic as it is, I have gone from having an institution problem, to working in a special education environment. It seems like a paradox, but I need structure and change in equal measure to thrive. Working part time alongside my own creative practice and researching, gives me that.

For over 25 years the ceramics room has become my sanctuary, I have a need to be near clay and endeavour to create an environment for others to explore its wonders, the sense of joy it gives to others is palpable, I try to create an environment that many others can come and feel safe to engage with the clay in all their different ways.

I was interested in art psychotherapy and had a dream to become an art therapist. After a few years of training at foundation and master’s level, I was overwhelmed with ambivalence. I experienced over-identification with the people I was working with instead of empathy. The head of the course described me as a wounded healer, but my inability to tolerate the intensity of one-to-one situations resulted in my choice to try a different route, returning to research from a more phenomenological approach rather than psychological, from the source, reciprocity and conversation directly with the clay.

When I began my research journey before 2016 there was very little information about neurodiversity out there. It was in tiny pockets as people were beginning to make connections and open up the conversation, now things have opened right up and the thinking and language around the neurodivergent nature, being and language is in constant flux and has become mainstream conversation with a lot of celebrity and negative media attention

You could say that it is a good time to be born in relation to neurodivergence, as I feel we are on the cusp of change but as Audre Lorde said in her 1960 talk at a conference in New York We must throw away the master’s tools as the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. It is important to change our perspective on differences as a society, appreciate and celebrate the bounty of expansive thinking that the diversity of being and thinking brings to the world.

How do you create the feeling of ‘frozen moments in time’ within your sculptures, and what do these moments reveal about the human experience?

I retreat into my own world of ceramics, away from the confusing social world, stimming as a way of meaning-making. I create vignettes, recreating scenarios, frozen moments, like a still from a film set. The instillation I created for AWARD British Ceramics Biennial 2019, incorporated a few lines of the same story. They were things I would rather describe in objects than words. That is the point, people can read the work and make up their own minds up about the pieces and the overall work, based on their own experiences. Some of the ideas they take from it would be the same and some would be different.

How does your work connect to broader themes like our relationship with the environment and the world around us?

We need to come at it differently; Diversity is an important part of neurocognitive variation. Perhaps through less discriminatory awareness and understanding of neurodiversity there may be a movement towards healing ourselves and the planet through creativity, activism and craftivism. As Chris Packham stated: “We need people who don’t see boxes, neurodiversity is an inbuilt important part of our species. We are all manifestly physically different and we need variation in our species as resources change. Neurodiverse people have been shaping our civilization and maybe that’s why we are there.”

So, neurodiversity is as essential as biodiversity, they run parallel. We are the earth, we come from the earth, from clay, we belong to the earth, but we have forgotten.

The Covid pandemic forced people to take a step back through a period of self-reflection, people reengaged with their surroundings at a slower pace, recognising themselves in the natural world and woke up to environmental issues. Social media exacerbated this growth in self-awareness, questioning themselves and their place in the world.

The concern that I am adding to the environmental problem by creating more stuff destined for landfill is always with me. I buy glaze material and clay trimmings from potters who do not have the time to reclaim their own, it has become a part of my process as I work a lot with paper clay, so will start with dry clay and work it into a malleable state for creating. I fire to lower temperatures, make smaller objects and use the different colours of clay rather than glaze and utilizing the naked skin surface.

We are becoming more aware of differences in neurocognitive variance, sensory perception. Emotion, feeling and the importance that these differences have for humans. The different ways of being and divergent thinking, which may result in more creative ways to tackle the problems of our world in crisis.

Do you see your sculptures as offering a kind of release from anxiety, or are they more a reflection of it?

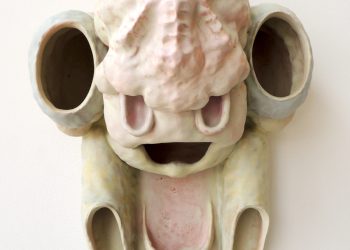

They are both a release from anxiety and a reflection and representation of it, as my process of making is an immediate way of working things out, of regulating myself through stimming and ‘telling to the clay’. The clay’s skin-like properties emulate my own skin, responding to my own breathing, actions, and thoughts, making those intangible experiences of vulnerability, sometimes with dark humorous undertones, into tangible forms.

My MA ceramics work at Cardiff Art School explored this sense of uncertainty and the weight of being in the body. The pieces represented sweaty, clammy skin and skin crawling and goosebumps through the glaze qualities created from multiple glaze applications of porcelain clay shrinking and crawling away from the body of the slip cast bodily forms. These were responses to electrified and highly stressed situations, What Francis Bacon called The violence of the real.

In what ways do you see your work as challenging conventional ideas about figurative art or the body in contemporary ceramics?

We all have our voice, this may not always be in words, but performance, activism and more. My voice is through clay. I create ambiguous sculptural figurative forms, narrative, and dialogic objects, to encourage curiosity rather than shouting it at you. I am asking people questions about themselves, whatever response whether through curiosity, humour or disgust, through the visceral and human nature. To question what it is to be human today and how we are all different and the same. How we fit and don’t fit together in the society that is made for difference but not designed for difference. I am representing the different aspects/parts that make up the self, we are not fixed but are mutable and in flux, ever changing, growing and shifting, responding to our environment, creating and recreating the self visually like an exquisite corpse.

My work is not about the image of the body. My first creations in clay were figurative and were about my confusion, I always created ambiguous anthropomorphic unusual forms related to the body which became more stylised over time, then one day I questioned what I was doing and made a change.

The body has been used to tackle many different aspects of the human experience, although as far as I am aware I am tackling a subject area that has not been approached before in the same way. I am expressing how it feels to be in a neurodivergent body, the psychosocial experience represented in amorphous, ambiguous bodily forms. This is not confessional art or tragedy stories, but a real experience of living in this body within contemporary Western culture. As Donna Haraway put it, I am Staying with the trouble.

Interview with Rossana Martin

What draws you to the marks and alterations humans leave on the landscape, and how do these influence your art?

My childhood was spent making visits to my grandparents’ sheep farm every Sunday, where we would walk across the fields and down to the site of a former brickworks. The brickworks existed from 1891 – 1907 on the foreshore of a tributary of the River Fal. The brickmakers dug clay from the river bed and used it to make and fire bricks in beehive kilns before sending them off to build houses in Truro and Falmouth. The clay that was used came to be there after being spilt out of the china clay extraction pits on the western side of St Austell. Hundreds of thousands of tons of waste clay were lost to rivers due to rudimentary refining processes. It settled and silted up the river bed, layering on top of river mud to create a bright white clay flat when the tide was out that sparkled with mica in the sunlight. As children, we would run, skate and slide across this mud as if our feet were ice skates, and we would swim in the river channels, making chutes in the clay banks and splashing into the milky water.

This early exposure to a very specific waste material has informed my practice to a great extent, unconsciously, I think, for a while, but becoming much more conscious over the past decade. Learning more about how the clay had come to settle where it was, and the processes involved in that transformation of material fascinates me. The impact the china clay extraction industry has had on the landscape in Cornwall is phenomenal, and the new landscapes that this human activity has created are beguiling and somehow full of potential.

What role does materiality play in bridging the connection between people and the landscapes you explore?

Materiality and the craft processes involved in understanding a material play a huge role in creating opportunities for connection between people and landscape. A lot of the ex-extraction land is privately owned by the extraction company and is off-limits to the public for safety reasons. This can make the landscape feel wild, ominous and alienating. With the wildness comes an opportunity for plant and animal life to flourish, and the landscape that has been made out of waste quartz sand from the industry is now creating new ecosystems and habitats. Learning about how the materials came to be in the place they are provides insight and understanding, but being able to actually make something out of and transform those clay materials into fired glazed ceramic using materials that have all been gathered from within walking distance generates real wonder.

How do participatory projects deepen the impact of your artistic practice, particularly in engaging communities with environmental themes?

My practice has always involved an element of participatory work, and yes, I believe engaging with and creating communities of people around a shared interest is an incredibly important way of being in the world. Working together provides an opportunity for shared learning and pooling of knowledge, which allows openness and creates space for discussion. I find that when people are making with materials they have collected themselves from the local landscape, there is so much to talk about. Gaining the connection with that material provides an opportunity to talk about some of the more difficult and complex themes around our use of materials, their importance, and how we can challenge anthropocentric thought by deepening our understanding of materials and where they have come from.

Do you see your sculptures as a form of commentary on humanity’s reshaping of the Earth, and if so, what message do you aim to convey?

Yes, my sculptures have been made using ‘waste’ materials from the china clay extraction industry. In part, they are demonstrating the creation of something out of an undervalued material resource. My current work is asking whether the making of sculptural tools and apparatus using regionally specific waste materials can generate new instances for life-affirming connections, both between people and between people and materials. Underpinning that question is a belief that creating a space for playful and imaginative connections is increasingly important, as though that can come new knowledge, understanding, and respect, whether that is for each other, ourselves, or the planet.

Interview with Jane Millar

What draws you to explore the unseen energy within ceramic objects, and how does this idea shape your work?

The ‘unseen energy’ relates to the hollowed, but not ’empty’, space inside a clay object that is required for it to fire successfully. However, this comment I made relates to much more – the invisibility of our inner lives, made partly visible in made objects, and the relationship of an invisible interior to a visible exterior. My work deals with my fascination with what psychotherapeutic writing calls Object Relations – the endlessly negotiable and creative space between what we perceive as us – ‘inside’ – and others, or the world, outside. My work plays in this zone – a space of becoming, liminality, revelation, imitation and echoes.

How do the chemical transformations in your materials, such as oxides and silica, contribute to the narrative of your work? and 3. How do the textures and surface qualities of your pieces express the tension between interior forces and exterior energies?

The use of heat, chemicals and materials, glazes and oxides, point to a surface manifestation of both what is within, and where it meets an Out Side. In this respect, I often feel that ceramic surfaces can present a face of some kind. Our own faces may present a social and constructed self to the world, masking our interior energies, but others can often read what is within. This is where the tension lies. For me, the fired, reactive, and often barely controllable qualities of materials subjected to heat can be a revelation which takes place out of my direct control.

Your works evoke a sense of both fragility and resilience—how does this reflect humanity’s relationship with the Earth and its resources?

This is a lovely question – thanks! Our sense of our physical and emotional vulnerability, our experience of joy and suffering as we age, along with memory and imagination, is the basis for human empathy. This is a learned skill, I believe, but crucial to shifting our position in relation to more-than-human life in our biosphere. If my work can convey objects as experience and emotion in life, and if possible, can evoke empathy for the fragility of our biosphere, which we are absolutely subject to, then I am happy!

What message or feeling do you hope viewers take away when experiencing your work in the context of Earth Overshoot Day?

I read, watch and listen to everything I can about early humans, and particularly, early hominin species. The only surviving hominids today, though not necessarily the most successful, are Homo Sapiens – us – due to a creative revelation within our brains and bodies as a consequence of ancient climate change and human nomadism. In other words, our extraordinary creativity and adaptability are something that has got us into the current mess! Donna Haraway’s term (and title of her book) is ‘staying with the trouble’. For me, this suggests persistence and curiosity about the living world. It’s also about adapting materials and technologies in both a new and old way to protect the world and the survival of life in it. It is also, over everything else, about cultivating and practicing tenderness for the world.

Interview with Jacqui Ramrayka

How does your work with clay help you explore and express ideas of identity, home, and belonging?

I use clay because that’s my voice, my material- I’m thinking through my hands; for me, it is the only medium that can embody all the themes in my work due to its immediacy, how it responds to touch, recording and remembering every action like a haptic diary.

My current work explores ways to articulate notions emerging from the themes of memory and grief and my Indo-Caribbean diasporic identity, which, particularly since the Windrush era, has morphed into a hybrid crafted by different cultures.

My focus is the ceramic vessel because it is a signifier (container for meaning and ideas) and a powerful form (imbued with a history of sacred and domestic rituals). Vessels can be seen as a metaphor for the body/self, separation and entrapment – but also for holding together to prevent things from being lost or forgotten.

I’m looking at how objects can embody concepts of memory and identity, exploring connections between personal and collective memories; trying to give form to something intangible using residue and remnants, fractures and erosion, to embody fragments of memories, decay and time.

Why do you choose porcelain as your primary material, and how do its qualities of purity, fragility, and strength reflect your themes?

The history of porcelain mirrors that of the Indo-Caribbean diaspora, as it’s a story of migration and reinvention. ‘White gold’ is also a common thread – both sugar and porcelain were described as this because of their scarcity, hence value. I explore hidden narratives and layers of memory through unwrapping stories associated with evocative objects, working towards new pieces inspired by the personal stories gathered through my recent ‘clay and conversation’ workshops at the V&A, MoMA, and the Gardiner Museum.

How do the landscapes that inspire your work influence the way you think about our relationship with the environment?

I hope my work will help viewers make deeper, unexpected connections with these evocative materials and will demonstrate how fragments pieced together can be combined to tell a much richer, more poignant story of how the impact of double diaspora is felt in everyday life, and to disrupt/challenge familiar narratives/tropes.

Introduction and interviews by Vasi Hîrdo, Editor in Chief of Ceramics Now Magazine.

The Whole World In Our Hands is on view at The Stephen Lawrence Gallery, London, between April 12 and May 17, 2025.

Subscribe to Ceramics Now to read similar articles, essays, reviews and critical reflections on contemporary ceramics. Subscriptions help us feature a wider range of voices, perspectives, and expertise in the ceramics community.

Photos by Monwar Hussain.