By Brigit Connolly

In 2022, Anne-Laure Cano and Jim Gladwin – two artists who work with clay – began working together towards an exhibition at the Museu d’Esplugues in response to, or translating from, the historical remains of the Pujol I Bausis (La Rajoleta) ceramics factory near Barcelona and its extensive archive. Founded in 1856 near a clay deposit, La Rajoleta made architectural and industrial ceramics for over 100 years until it ceased trading and fell into disrepair in the second half of the 20th century. During the late 19th and early 20th century, it was famous for its production of art nouveau and modernist ceramics commissioned by architects and designers including: Gaudí, Domènech i Montaner, Puig i Cadafalch and Gallissà. These pieces can still be seen in different areas of Barcelona, such as Parc Güell, or in buildings like Casa Lleó-Morera or Casa Amatller and at the Pere Mata de Reus Institute.

How did your experience of working on this project change your work?

Anne-Laure Cano: Through my work, I explore themes of memory, identity, and sense of place, so initiating and working on this project was something I had been dreaming of. I’ve wanted to work with an institution for a long time and had been trying to find a way to approach a museum or institution to work on their collection. La Rajoleta seemed the perfect place. It created a framework within which I could work creatively. I found that I had to work more as a researcher and creatively use these methods. This recalibrated the relationship both with the work and audience. Until recently, I’ve worked on individual pieces shown in galleries or competitions. The project and exhibition allowed me to initiate and maintain a dialogue with a collaborator and collection, to think about how to connect and communicate with an audience in a different way. I’ve worked on a larger scale and developed installation as part of my practice.

Jim Gladwin: In some ways for me it was a strange, alien way of making, responding to something that’s already there. My work comes out of clay, the material. But for me, having the connection with the factory, being able to hold some of the things that they used to make created joy and opened new ways of looking. It was fantastic to have that connection to think about the people that worked in it, their processes, methods and materials. Industrial production is an aspect of ceramics and society that’s often ignored, but it’s crucial. Traces remain in the archive, architecture and fabric of the urban environment and we wanted to contemporise this.

The project, which you called Translate: L’Ofici Ceramista (The ceramicist’s trade or metier), seems to encompass various modes of translation. It moves between languages, media, time and place. In English, as I read it, Translate could involve an action and an imperative, or a suggestion to the artist and viewer that they translate.

A-L C: We gave a lot of thought to the title, which word might we use, in which language, what we wanted it to say, and what this might communicate. Jim suggested the word, Translate. For me, the title, which is not in my mother tongue, wasn’t an imperative at all. It was just an infinitive, so it was more neutral. It described our experience, the process and act of translating from our source of inspiration (museum, factory and archive) into new work. We struggled working between the four languages, but ultimately decided not to translate the title into Spanish or French or Catalan, but leave it in English. I find translate broader in scope than traduire, for example, which refers to translating word-for-word between languages. In English – it sings – is more open to other possibilities or nuances and communicates exactly what we wanted to say. The subtitle: L’Ofici Ceramista, remains in Catalan, so people who don’t understand English can understand that the exhibition is about the metier of the ceramicist.

J G: For me, it’s less of an order and more of a question, or invitation, asking people to think as they engage with the show. Hopefully, it made visitors think. Also, it’s short and to the point in that it describes our process while working towards and thinking about the show. At a pragmatic, functional level, we worked between languages: Anne Laure speaks French, I speak English, the museum and archives operate primarily in Catalan, but also in Spanish. When we were doing our research, we had to negotiate the slippages between these in terms of the languages the archives and factory records used to name equipment, technical processes and materials. So, in that sense there was also an imperative, in that there was a job for us, to work from the records and remains of the factory and translate from these into our work. But it’s also a verb and, as artists, I think it’s something we do naturally in our creative practice, we translate ideas into, media, into three dimensional forms.

Let’s discuss – or refract through the prism of translation – some of those thinking and making processes, the connections made through your work that continue to inform it and underpin your choice of title. Acts of translation involve working from an origin that asks to be translated, transported metaphorically or literally elsewhere into another text, medium, object, location, culture, or time. What did the origin you worked from ask of you?

A-L C: We worked from the remains of a factory: it’s museum and archive. Jim and I have collaborated on previous projects, so after I won the Pujol I Bausis Prize, at the Angelina Alós International Ceramics Biennial of Esplugues at the Can Tinturé museum (2021) I had a good conversation with Carme Comas Camacho (Director of the Museus d’Esplugues de Llobregat), who was quite open to my suggestions. She was keen to recalibrate the relationship of visitors to the museum and thought that it might benefit from other ways to engage and help them understand more about the processes involved in making the ceramics produced at La Rajoleta. They were interested in using artists in residence to make an exhibition that responded to their collection. In many ways, Carme gave us free rein, but she did have an objective in mind in relation to how the exhibition might help to inform the audience. From our conversations, I began to understand our role as artists to be more like one that accompanies the audience in a process toward understanding more about the different forms and amount of labour involved in the work of a ceramicist, when making a clay object or sculpture.

J G: In terms of source, there was clearly a job we had to do: to respond to the collection, to work from the archive, to bring into focus the people that worked in the factory.

A-L C: Yes, we did want to bring attention to the workers and their skills and see if we could incorporate the local clay that had been used by the factory. Clay is at the core of Jim’s practice, and he was particularly interested in using the local clay. He had sourced and experimented with clay from the region years ago and given me ideas where to find it when I first moved to Catalunya. Sadly, it was too difficult for us to make this part of the project.

J G: Yes, we looked into this, and it was a big part of our discussions. Carme showed us the old clay pit, which is still there, it’s massive, but now it’s a park. The clay is good, but it wasn’t possible.

There are often questions around how faithful a work of translation is to the original. Or to put it another way, how much the translation may have distorted or altered the original during the process of transfer to make it fit with a particular viewpoint or stance. For example, you have both had very different cultural experiences to the people working in the factory: you are English and French, you are artists and you live in a different century. Inevitably, your background influences how you responded to and worked from the museum collection, archive, and factory. Did this create moments when you questioned what you were doing in your work and how you were doing it?

J G: I think there was actually a lot of this going on. As artists, we work creatively, so inevitably we impose our own ideas and personality onto the project. And yes, those question marks arose as we worked. We consistently asked ourselves if we were doing the right thing. In making connections from the archives, we were aware that these were formed by our views on the source material, and we kept questioning if we were bringing too much of ourselves into it. But we weren’t trying to translate in the traditional sense, we were translating creatively, so there was more freedom. But that’s another reason why I liked the title in relation to our project, because it alludes to and questions these factors in the work translators do, how their own personality and culture inflect as they work with the source material to form part of a new creative production. We were working within this too.

A-L C: The way I thought about it in relation to my work was similar, but a bit different. For example, I did not want to faithfully reproduce the factory-made ceramics we explored in the archive and elsewhere. The ceramists working in the factory achieved perfection. I didn’t see how I could strive to attain that form of perfection… and any way probably fail. Pursuing this goal wouldn’t add much to the conversation we were having between past and present. That isn’t the way that I work. So, in my translation I tried to be faithful to the emotion I felt when visiting the archive collection or when reading about the factory work. Essentially, I was translating my experience of trying to get closer to the factory and the workers into a new body of work. This experience changed my own artistic language. I’ve always worked with high firing clays and glazes, but to get closer to the workers and the materials that they worked with, I started to use low firing clay and earthenware glazes. This meant I worked with a completely different palette and developed a new register to express this.

How did this make you feel?

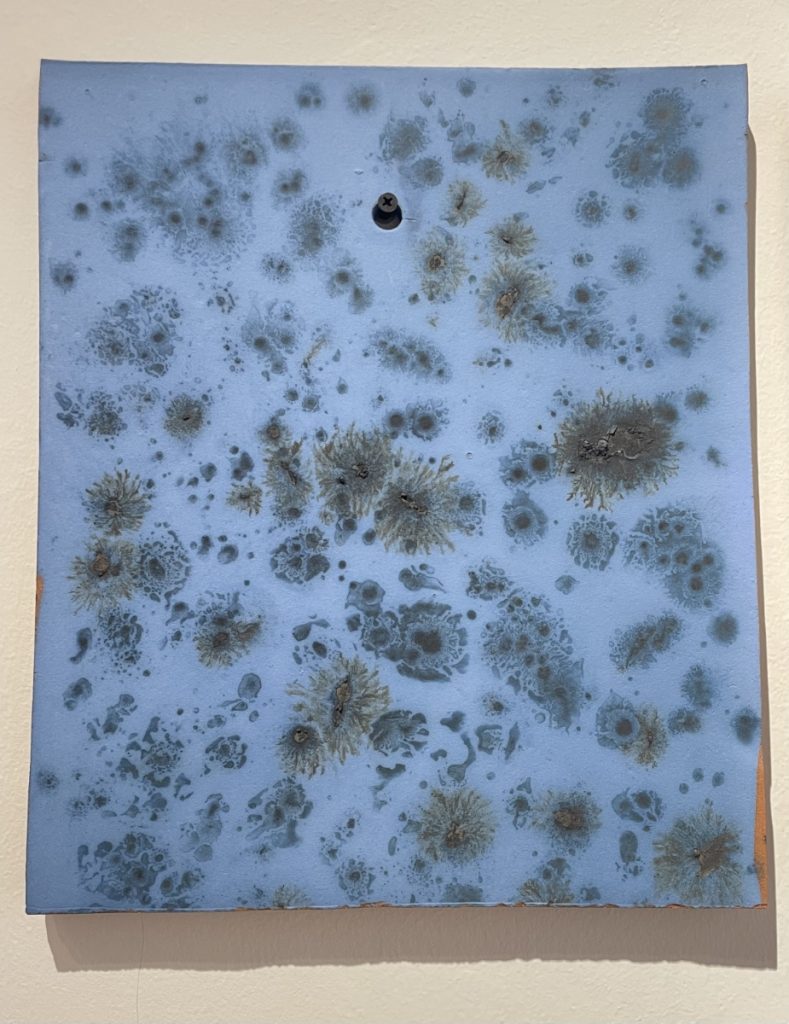

A-L C: I was terrified at first. I was overwhelmed by the archive. By the quantity and quality of the work, the perfection, and human imperfection, the sense of responsibility, or desire to honour these people and their work. Finding a way to translate these emotions and discover a new vocabulary, with a requirement to deliver work for an exhibition, felt vulnerable. But I also wanted to take risks and embrace this opportunity to push myself. It’s opened my horizons, I’ve learned a lot. My installation pieces Inventar-io and En Proceso grew out of this experience. Inventar-io is comprised of tests and draws on thousands of tests made by workers in the factory. En Proceso takes this source of inspiration back into my studio, into the bedrock of my practice by displaying on shelves beneath the five finished sculptural pieces the tools, clay and the maquettes that became integral to my creative process on this project.

J G: I also wanted to retain some of my usual way of working in the project and to work in a way prompted by the collection; that was very different from my own work. The pipe piece I made drew directly on the factory’s bread and butter, core production of structural ceramics. These aren’t like the fancy, expensive, ornamental ceramics the glazed tiles, finials and sculptural pieces commissioned by architects that you see all over Barcelona. They’re functional, vernacular forms and would have been churned out by factory workers using moulds and extruders. Today we see the same forms in plumbers’ merchants. They’re made in plastic now, but they used to be ceramic. Salespeople would carry sample boards of these forms: S-bends, T-bends, U-bends in miniature. I don’t often use extrusion in my work, but for this project, I wanted to work from these and play around with extruded forms using slip and bits of glazing. So, for us translating, working from a source was positive and prompted new ways of making.

Translators often claim that their role is to step aside and let a source communicate or speak through them. What you’ve both just commented suggests to me that in working towards this exhibition, you were conscious – as artists – of working like translators, of making yourselves, your own visual language, registers, modes of expression less visible… Perhaps assuming the role of working more like mediators between the collection and the exhibition. Is this the case?

A-L C: I have my own voice when I make individual sculptures, but this project gave me an opportunity to explore something else. It felt like this project was its own world, separate, apart, so I tried to adapt, be open to learning and new ways of making and didn’t push my own voice in the same way. In some ways, this felt like a safe way to work to say something completely different from what I say when I make my own work. In my individual pieces, I always want to work through and communicate something in particular, but with this project I questioned whether I could force my habitual way of working onto it. It was another conversation entirely.

So in some ways, the title and its subtitle are indicative of your intent to step back and bring attention to or give voice to the hidden or lesser-known aspects of the factory and its history. The people, their skills, techniques and materials used that are embedded in the finished product.

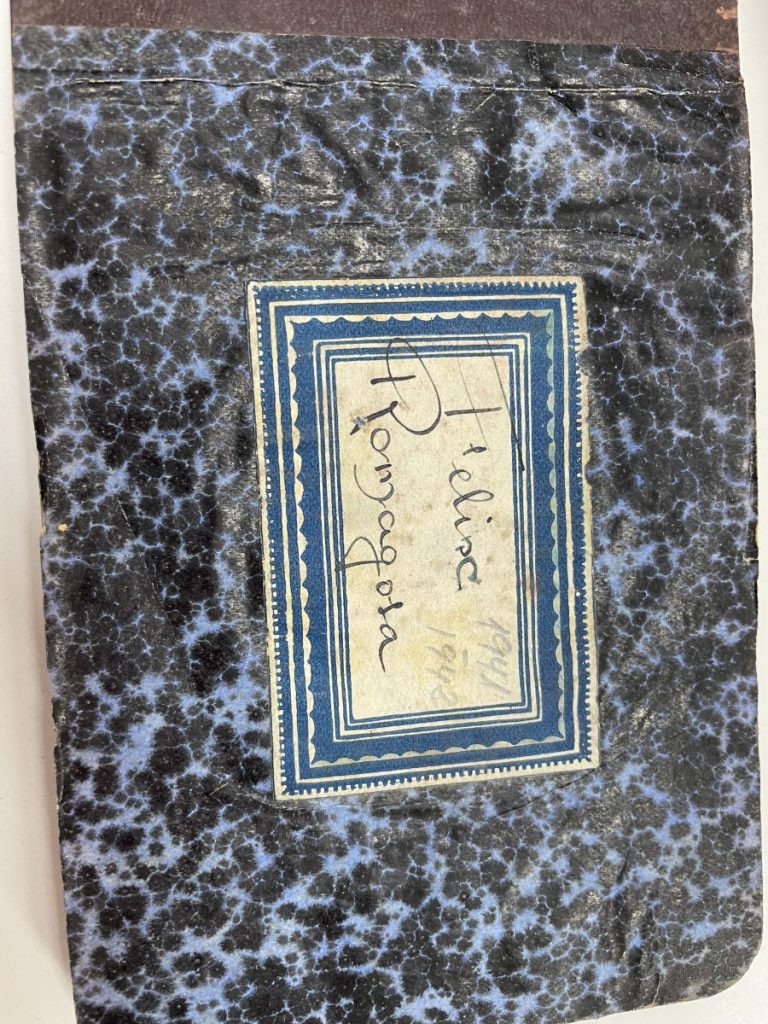

J G: We both felt a deep sense of responsibility towards the workers. A haptic, tacit connection to the people whose labour produced the ceramics that we see in the fabric of buildings around Barcelona and beyond. We could have spent years researching in the archives and the thousands of glaze recipes, orders for materials shipped from all over the world. We read names of factory workers, saw their handwriting, their time sheets, logbooks listing their jobs and the tasks they did each day.

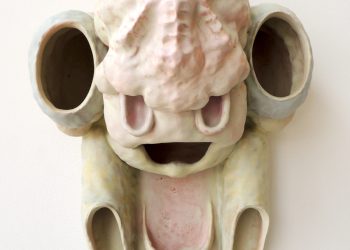

We didn’t want to be too literal in our approach as we made work about this, but there was a real sense of loss. The loss of humanity, of lives and community that had developed around shared skills, knowledge of material and technical expertise. We wanted to find a way to bring out these embedded histories, or hidden voices that wouldn’t compromise, or undermine their authenticity. For example, citing people’s names would have been too obvious and maybe too superficial or tokenistic. For me my way into this became quite simply about finding a way to show the making, to bring attention to the fact that human hands had made the work in the factory. So, my pieces are all about the hand, the mark of the maker. I don’t try to hide finger or thumb prints. These points of contact with the clay form it and become the decorative feature. The tablets inspired by the covers of logbooks create these connections for me, as do the pipes and the flower pieces.

Brightly coloured flowers are not something I would usually make, but I used my fingers to form these flowers. If you look closely, they are entirely made of marks. It was also very important to work from the archival records of raw materials the factory workers used to develop surfaces and glazes. For the flower piece, I wanted to recreate the luscious, brightly coloured, metallic copper greens, cobalt blues and iron-rich honey glazes that only lead can deliver.

A-L C: Sadly, there isn’t enough information about the factory workers. My work was more about their absence, the fact that they had disappeared, and that we forget them. There is a stark contrast between the millions of tourists who come to Barcelona each year to visit attractions like Park Güell and La Casa Batlló and engage with this side of Barcelona’s cultural history through these visible vestiges of its ceramic production and the total ignorance of where those ceramic objects were made, with what materials and by whom. My pieces: En Proceso (In Progress) and 8 pesetas 64 centimos ya es jornal (8 pesetas 64 centimes is a day’s pay) all derive from their absence. The are intentionally left unfinished, and I use this lack of completion to evoke this sense of loss.

In a sense, all that can be drawn are provisional boundaries or lines in the sand. As I have come to understand it, acts of translation are a manifestation of the engagement of the mind with that which resists easy understanding. By nature, this is a creative, infinite task and as such precludes completion.

“….. there is no ‘original; which is not also a translation – ad-jointed to a prior text which lives on with it, because of it; indebted for its own life to another text which returns life as a result of it: calling for a complementarity and supplementarity which it also gives. This means that ‘originality’ is always divided from itself – since it is only as a translator that every supposed creator originates, fails, falls, and calls for translation in his/her turn. And it is through the supplementation and completion of an original text that the translator ‘extends, enlarges, makes grow.”1

Brigit Connolly is a prizewinning artist, researcher and educator. She holds an MA in Ceramics and Glass and PhD in Critical and Historical Studies from the Royal College of Art. Initially trained as a linguist and translator, her PhD thesis explores the development of theories and practices of translation intrinsic to artistic practice. She is course leader for the Ceramics Diploma at City Lit in London.

Translate: L’Ofici Ceramista by Anne-Laure Cano and Jim Gladwin is on view between November 7, 2024, and May 25, 2025, at Museu Can Tinturé, Esplugues de Llobregat, Spain.

Subscribe to Ceramics Now to read similar articles, essays, reviews and critical reflections on contemporary ceramics. Subscriptions help us feature a wider range of voices, perspectives, and expertise in the ceramics community.

Photos courtesy of the artists