By Nigel Atkins

Put simply, this is an exhibition of Pekka Paikkari’s ceramic art deliberately set among one of the most extensive permanent collections of Gallic and Mediterranean pottery in one of France’s most delightful provincial museums. The Ensérune Archaeological Museum crowns a rocky outcrop some thirteen kilometers west of Béziers. In 2022, the Museum enjoyed a brilliantly designed renovation and is now one of Southern France’s major cultural gems.

That Pekka should be exhibiting in such a dedicated space is due first to happenstance, a surprise discovery in 2023 when the artist was showing his work in the Gallery at Le Don du Fel, and then the intuition of the Museum’s director, Lionel Izac, who saw in Pekka’s art the possibility a rare accord between contemporary creation and archaeological reality. That an internationally renowned Finnish artist should include in his vision of the present such a powerful evocation of a distant past convinced both the Museum and the Centre des Monuments Nationaux of the interest in mounting this exhibition. What better way of constructing a dialogue between the present and the past than exhibiting the works of this visionary from the far north alongside the Museum’s permanent collection?

Indeed, the fundamental concern of Pekka Paikkari has always been to place his works in a temporal perspective far broader than that of just the present day. As a result, both because of his philosophical intentions as well as his mastery of the art of fragmentation and reconstruction, he has developed a formal language akin to that of archaeologists themselves, of whom it could be said that an important part of their craft could well be summarized as the purposeful reassembly of shards from the past.

The exhibition is deliberately divided up between the main temporary exhibition room and the rest of the Museum, with here and there the installation of different monumental assemblages echoing those of the Museum, while throughout the different rooms small poetic proposals are set in showcases. Elsewhere, the artist places sculptures that cleverly take up the theme of the contents of the showcase, which he is only temporarily replacing. This is indeed his project, first to confound the gap of centuries and then to put the spectator before the obligation of a real commitment to his own perception, to decide where the value really lies. Is this carefully preserved and restored everyday pot from some two thousand years ago really more interesting, more culturally charged than this ceramic can that could be unearthed in the distant future?

When we see the works of Pekka Paikkari for the first time, whether it be his XXL wall panels or his richly coded sculptures, we are confronted with an experience, both cultural and ceramic, far beyond our usual field of references. We are overwhelmed, again and again, by an unprecedented wave of questions. Feeling this insistent demand for answers is both refreshing and deeply nourishing. It immediately engages the intellectual curiosity of the viewer and ensures that the artist’s work is classified where it should be on the Altiplano of contemporary ceramic art.

If you want to be analytical, it is probably best to start with his wall panels, which, in many ways, are the most openly accessible part of Pekka’s repertoire. Also, because the freely-worked clay impasto of their fractured surfaces holds an important key to the interpretation of the artist’s intriguing formal vocabulary. So why all these fractures, and how are they done?

Once Pekka decided to move away from the potter’s wheel and the dimensional limits it imposes, he was then confronted with those imposed by the size of his kilns and then by the physical properties of the clay itself. When working with a large sheet of clay, you quickly discover that you cannot go beyond certain dimensions without risking uncontrolled cracking and undulations.

The initial discovery was caused by abandoning a small still-wet panel over a weekend because of unexpected family demands. Returning to the studio two days later, the panel had dried and cracked all on its own, and a new, limitless way forward had been born. What Pekka saw was the obvious solution for making panels of any size. All he had to do was adopt the crack as a welcome advantage, as a visually structuring element. The initial objective was to get rid of dimensional limitations, but the final result was the discovery of unsuspected freedom and the birth of a new and dynamic tension between the potentialities of clay and the newly extended pictorial space. Before Pekka’s invention, no one had ever seen ceramic panels as large or as bold, and certainly never so light.

How does he make them? On the floor, always, like the abstract expressionist painters of the 60s. There, he can see everything, free up his gestures, and use his body weight to enable him to engrave the sweeping fields of ridges that give his surfaces the appearance of soil freshly harrowed. The slips and glazes are also applied while the panel is still lying damp on the floor. After that, the fracturing of the whole into its different parts is simply a matter of drying, opportunity and skill.

The panels are very thin, five to six millimeters, hardly more. Once broken, essentially by contraction during the rapid drying, the individual parts are fired just once before being mounted with resin and industrial sealant onto a plywood support so that when finished, the panel is both rigid and easy to handle. Sometimes, for larger formats, the panel is mounted on a partially visible wooden frame, so that it also can make its contribution to the overall composition. Pekka likes to say that “Break, and break again, then reassemble!” is the key to his way of working. That may indeed be true, but what is clear is that his fragmentation of large areas, clearly unrelated to any Schumpeterian delights in creative destruction, has endowed his process with quite exceptional and unexpected creative opportunities.

This is because the network of cracks, a bit like a web of black mastic kintsugi gives the surfaces of his works their surprising structural cohesion that reminds us of the unifying role of the lead cames in the construction of stained-glass windows. This is indeed a delightful parallel because it conveys a deep sense of the fragility and impermanence that haunts all human effort, while at the same time nurturing a dialogue of great originality around the format of the artist’s surfaces and their improbable ceramic identity. Here, we can sense a suggestion of conquered impossibility as well as the notion of the birth of hope.

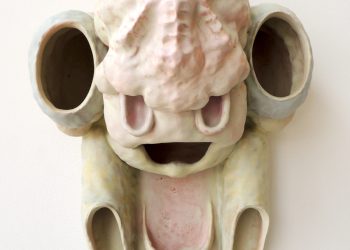

Turning to the sculptures of Pekka, one perceives even more clearly the underlying themes that irrigate all his work: the paramount importance of embracing the unknown, the urgent need to invent alternative forms that question the established canons of physical beauty, and a wilful dependence on everyday forms to underline the relevance of the cultural heritage that lies at the heart of every piece of crockery, past or present. If we are to construct our own contemporary mirror, we might well do best by recognizing the essential cultural validity of the humble object. As you can see, all those the artist uses to build his monuments are wheel-thrown and roughly finished, in part to exalt the idea that they all belong to an unidentified past, but also to insist on the intrinsic bond between man and matter, before industrial alienation became the necessary companion of humanity.

Another important element in Pekka’s sculptural vocabulary is his repeated use of shards, of broken ceramic elements, of the incomplete. All fragments imply the existence of a whole so why incorporate into a sculpture a complete entity when an identifiable part will do the job, will cite not only the whole but also the drama of destruction, and dramatize the ensuing sense of loss. When put like that, the discursive as well as the emotional gain appears as evidence that the brevity of a fragmentary foot-ring can mourn the tea cup, becoming an integral part of the sculptor’s formal language.

It is also important to remember that the artist’s entire opus is built on inventions that subsume a borrowed legacy, that of the indefinable relic, whose original use can no longer be determined. These are remnants, once the swell of time has receded. Thus, his sculptures, which may resemble perfectly recognizable objects, such as bottles or vases, can no longer, due to their format, or surface treatment, or even because of their accumulation of other elements that they have gathered during their construction, be identified as such. They stand before us as incomprehensible findings, coming from a past both unknown and unrecognizable, as if they had just been discovered on an archaeological dig. They are no longer bottles or vases, because all notions of utility have been removed. In many ways, these works are composed of functional pots shorn of their utility but still potent vectors of the values they so steadfastly upheld.

Curiously enough, and almost independent of the size of the works in question, each panel, each sculpture seems to be endowed with the stature of a monument, at least in the memorial sense. It’s as though the artist is insisting on celebrating the importance of remembering the present. Whether he’s proposing a small composition of tin cans, a weathered curiosity bottle or even a stack of fused mixing bowls, we can clearly discern the common denominators, the need to document the comportment of the present, to witness a sense of desolation concerning the past, and finally an evident anxiety for the shape of the future.

If you think these works are too cleverly coded, please remember that in a not-so-distant past, the idea of easily appropriating the significance of any artwork was seen as a sign of cultural levity! For centuries, access to a cultured appreciation of classical sculpture was padlocked behind a whole matrix of different keys, initially mythological, later on religious, and finally simply moral. After doing away with this classic chessboard of codes, Pekka offers us an innovative framework of interpretation where references collected from our own experiences suffice.

Nigel Atkins is the co-founder of Le Don du Fel.

Pekka Paikkari: Fragments of History is on view between June 6 and September 21, 2025, at the Ensérune Oppidum and Archaeological Museum, Nissan-lez-Enserune, France.

Subscribe to Ceramics Now to read similar articles, essays, reviews and critical reflections on contemporary ceramics. Subscriptions help us feature a wider range of voices, perspectives, and expertise in the ceramics community.

Photos courtesy of the Ensérune Oppidum and Archaeological Museum