By Unu Sohn

There is the illusion that coming of age is a singular occurrence in a person’s lifetime. We each supposedly transition from child to adult and join a collective of fully developed, grown people capable of regularly changing the duvet cover and filing taxes. We know who the right person to marry is and how to cook a medium-rare steak. In reality, a person is coming of age again, again, and again. To experience life on earth as a human being is to constantly re-evaluate what I value, whether I am successful or fulfilled, what I need to change.

With the exhibition Self-Made: Reshaping Identities at the Foundling Museum in London, four ceramic artists demonstrate how clay is a particularly fitting material metaphor for life. As a substance, clay challenges duality: it is both wet and dry, soft and brittle, durable and fragile. There are many different methods of working with clay ranging from slip-casting to coiling, with the sourced materials interacting in infinite combinations, yet all undergoing the same chemical change in the kiln. The expansive nature of the material and discipline is evident within the walls of the Foundling Museum’s basement gallery housing Self-Made from November 15, 2024 to June 1, 2025. The four distinct personalities of the artists Phoebe Collings-James, Matt Smith, Renee So, and Rachel Kneebone are clearly evident.

Who are you? Even in a vacuum, this is a challenge to answer. To form your identity by weaving in and out of prescriptive labels like “good mother” or “working class,” which are thrust upon you by dominant institutions, further complicates the ability to answer such a question. It also gives life color. You explore the boundaries and hybridity of your existence as a full person moving about a world consisting of restrictive categories, and to assert your intricate self is an innately subversive act. Marginalized people are especially aware of this as they experience the space between who they are and who society perceives them to be in their day-to-day. In a form of trickle-up identity politics, straight white boys and men are now also experiencing this discrepancy first-hand.

The recent popularity of the Netflix show Adolescence is evidence of the contemporary critique of patriarchy and masculinity. The plot follows the story of 13-year-old Jamie Miller, charged with the murder of a classmate. Viewers find themselves confused, at times empathizing with the accused. The extreme story highlights the dissonance many young boys and men experience in the present-day climate as patriarchy attempts to reassert itself through toxic forms of masculinity after increased awareness and meager structural changes regarding diversity and equity. Adolescence particularly focuses on the use of social media and how this effects the development and socialization of children today. Is social media a unique form of the technology? It feels extra sinister but this view follows a pattern of society’s negative attitudes toward inventions: a letter to Louis XIV in 1680 described how the printing press created a “horrible mass of books that.. might lead to a fall back into barbarism,” a fear of electric doorbells, and the computerphobia of the 1980s. I am a statistic then as I find myself wary of the online world and new technologies. Perhaps it is no coincidence that I am a luddite insisting on using a four-digit code instead of facial recognition technology on my iPhone and also someone who works in a hands-on, timeless material like clay.

The field of ceramics attracts many artists invested in the tactility of clay and Phoebe Collings-James belongs to this camp. Sgraffito tally marks in her wall-based ceramic paintings in Self-Made are a way of marking time. A variation on this mark results in a suture, highlighting the connection between time and healing. Layers of white slip and glaze create dreamy washes of imagery that appear to mysteriously emerge from the recesses of the black clay surface. Sometimes, the carved portions of sgraffito reveal the black clay underneath, while other areas are concealed and the scratched surface is just perceptible through a creamy layer of glaze.

There is a sense of the past in the work titled Late or now of Jamaica, which was named in response to a token in the museum’s collection that was left with a foundling child in 1757. This mood is fitting for the material. As ceramicists often say, “clay has memory.” In the work Collings-James has created for the exhibition, the artist addresses the Foundling Museum’s historical connections to slavery, which is the case for many established institutions in this country. I was not familiar with the term “foundling” prior to visiting the museum. It is an old-fashioned term for a baby left by parents who were unable to keep them, then cared for by an institution. The museum was once the Foundling Hospital, which was founded in 1739. Establishments like the Foundling Museum were supported by wealthy benefactors whose riches were dependent on the colonial wealth that exploited and trafficked African children. In this context, Collings-James presents a compelling argument about how progress is made through generations but still remains a legacy of the past.

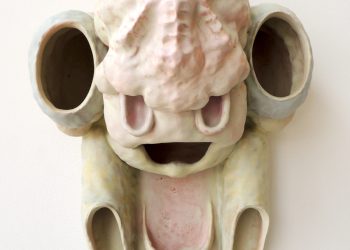

The artist Matt Smith also addresses how people, specifically the queer community, advocate for themselves within the confines and limitations of structures in place for decades or centuries before their lifetimes. Smith uses the slip-casting process to create surreal sculptures. In this method of working with clay, liquid form hardens as it dries in the plaster mould and then further solidifies in the firing process. For Smith, however, some of these moulded works are cast in a black parian clay that slumps and warps in the firing. Smith leans into this characteristic of the specific clay body, relating this to the queer bodies and identities that claim their own formations within and around the bounds of societal structures.

Other cast forms visually speak the same homogenous language of the 18th-century Spode moulds from which they were made, but up close these objects reveal themselves to be door handles made of teapot spouts and half-human half-animal chimera creatures. In the environment of the Foundling Museum and its history, these works reflect upon how historically stifling societal views that deemed queer folks and abandoned foundlings alike non-normative and fringe. They could also be understood as nonconformity passing under the guise of conventions. His earthenware meat platters depict the relational aspects of community within alternative families and romantic relationships. On platter features the women Fanny and Stella. This 19th-century duo were arrested for “disguising themselves as women,” and this piece of history unfortunately continues to be relevant today, after the UK Supreme Court recently unanimously ruled that women and men are defined by biological sex and Trump expresses similar views across the Atlantic Ocean.

In a time when we are seeing progress around autonomy overturned for queer people and women alike, the work of Renee So resonates. Her artworks remind viewers that such regulations on what was and is considered acceptable to larger society targets women and a sense of the divine feminine. In Mom Jeans II, So derives inspiration from an antiquated law that banned Parisian women from wearing trousers and “pretending to be men.” This law may not have been strictly enforced long after instated in 1799, but it was only formally removed in 2013. By invoking the denim material originally for workwear, this sculptural vessel addresses the freedom of employment and contemporary motherhood. In So’s work, freedom and identity are strongly tied to the body, which is neglected in our increasingly digital age.

A common thread in the ceramic works exhibited in the show is an element of the hidden: in the case of Collings-James’ work, it is colonial history and wealth. For Smith, it how queer folks deal with normative moulds. Renee So focuses on both the legislative and unspoken ways societies led by male leaders police women, while Rachel Kneebone’s Through a Glass series connects back to unnamed and even intentionally anonymous foundlings in the setting of this exhibition. Kneebone uses the cartouche, an ornate frame that traditionally contained the name of royalty in Ancient Egypt. In using this form as a departure point, and leaving the frames empty, viewers will recall the ground floor exhibition that overviews the museum’s history and the stigma associated with foundlings historically and today. Some of the stories shown are named, while others are anonymized.

Contrary to the title of this exhibition, the artworks of these four artists do not demonstrate a tabula rasa. The ceramic sculptures are less about self-reliance and more about contextualizing the struggle for agency in a society that has both past and present ties to racism, colonialism, homophobia, transphobia, and sexism. Each of the artists provides a glimpse of what is not being spoken and seen, perhaps erased.

Unu Sohn is an artist and ceramicist based in London. She holds a master’s degree in ceramics from the Royal College of Art.

Self-Made: Reshaping Identities is on view between November 15, 2024 and June 1, 2025, at the Foundling Museum, London.

Subscribe to Ceramics Now to read similar articles, essays, reviews and critical reflections on contemporary ceramics. Subscriptions help us feature a wider range of voices, perspectives, and expertise in the ceramics community.