By Joshua G. Stein

Objecthood is complicated. At first, we might assume that we easily know how to draw the profile of a tree. Maybe we understand that in the interest of time we might not be able to outline every single branch, every single leaf, or every single root, but with enough time we imagine we can trace this intricate outline. Yet we know that the intake of carbon dioxide and output of oxygen molecules through tree leaves into the atmosphere thwarts our notion of boundaries. Recent scientific studies reveal a “mycorrhizal network” composed of myecelium that connects trees with their neighbors to share water, nitrogen, carbon and other minerals, making it even more difficult to separate a tree from the forest, or even from its neighboring species.

And yet, we are not entirely wrong when we draw our simplistic profile of our tree. It’s objecthood is still partially intact. The practices of Del Harrow and Yonatan Hopp deftly examine the complexities of objecthood, neither stripping it of its discrete importance nor denying its dissolve into larger systems. In the work of both artists, distinct elements are rendered more so by their dramatic juxtaposition against disparate materials—a wood stick connects to a gooey blob of glazey clay or a ceramic stump sits atop a roughly-hewn wooden pedestal—but they still form parts of a larger art object. We know this because the elements anticipate one another through graceful arcs and radii that stretch out to meet their neighbors.

A tree as living force extends itself, reaching out with its branches, creating micro-climates under its boughs, ecosystems between its roots, atmospheres above its canopy. When one of its branches might fall to the ground, it might have an afterlife as host to many other species during its slow return of nutrients to the soil. Or, in a parallel world, this branch might become an object of another kind: a stick.

A stick is no longer a tree. Stickness requires being severed from generative life—vitality swapped for precise dimensionality. This severance offers a certain utility. It’s seeming lack of material agency allows it to be more versatile—it has no desires or predilections but instead it accepts. It can be operated upon. Its lack of a past equals more potential futures. Sticks are great for manifesting geometric patterns. Arrange them serially to create a screen. Assemble them to create a frame, a triangulated dome, or some other geometric shape.

A stick is no longer a tree. But does it remember its life as a tree? Should we? Stickness accepts material anonymity. “All the better to measure and describe you.” We assume a stick is made of wood, but it is inconsequential what species of tree it once was. Sometimes sticks are really carbon fiber.

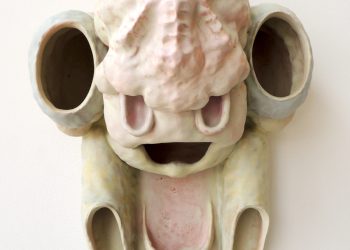

A stick can be used to measure, or in the case of Yonatan Hopp’s “Cobalt Network,” to describe and delimit space. Connecting and organizing these sticks are joints crafted in 3D printed and glazed ceramic. Hopp’s “sticky” connection points are precise geometric nodes, governed by the dictates of angles and alignments that require preplanning in both digital modeling and digital fabrication. Simultaneously, their material existence is “sticky” in a more intuitive way: it is the connective tissue that holds disparate elements into some larger cohesive whole. The strength of this stickiness is that it can negotiate the hard demands of dimensionality and geometry. Its own geometry is subservient to that network it has to connect. But however gooey and flexible this tar-like node might appear, the realities of ceramics—namely the fact that when fired it is not a very flexible material—necessitates a well-developed set of techniques to guarantee geometric precision. This has forced Yonatan into a set of continuing experiments to develop new techniques for maintaining precision in the production of complex forms. This involves innovating methods of 3D printing ceramic objects that have no flat sides to easily rest on a printing bed. Yet despite all the precision required to run multiple tests and prototypes and translate digital model to material artifact, it is ultimately the gooey and tar-like qualities of the node-object that are still primary. However much we might understand the role of these nodes as subservient to some larger geometry, the surface qualities of glaze, texture, and form demand all our attention.

If Hopp’s practice pursues the geometry of precision, Del Harrow’s pursues a geometry of abstraction. One of the themes that surfaces regularly in Harrow’s work is an experimentation with topology, the study of “geometric object properties preserved under continuous deformations like stretching or bending, without holes or tearing”. In sculptures like “Blue Knot,” “Vignelli (double yellow),” and the “Matrix” series we see a playful use of space that at some moments appears to be contained by a vessel form while at others it spills beyond it.

In Harrow’s “Tree” series, we are caught in a play between a topological complexity and a regression towards child-like figuration. Columns look like trees with branches while also appearing to be more abstract cylindrical tubes that have a mathematical relationship with the larger tubes from which they sprout. In a reversal of expectations, what might have been a simple pedestal, is instead a tree. This pine base most likely remembers its origin story as a tree, including its former life in the charred forests of the Colorado Rocky Mountains. Whether or not we know this backstory, we can sense that the base is not an inert plinth. It is connected to its past. It is bound to the ceramic tree-form above, formally responsive to its weight and presence.

In another sculpture, what looks like a tree does not meet the ground but instead shoots past or through the surface of the earth without touching it, instead merging with the underside of the base’s volume. This creates another geometrical puzzle where the tree is at once a part of the same topological surface as the base that it pierces through without touching. Space flows continuously from within the tree to the base and back out again. What might be branches trimmed back for winter, may just as well be a device to exhibit the continuous hollow within. Some of these pruned cuts align precisely with the envelope created by the base, asking us to read this as another geometric procedure—more aligned with the operations inside digital modeling software than the trimming a horticulturist might make. But the ambiguity is the point. In other work we find a simple species of figuration, where trees have the profile of trees, leaves look like leaves, and branches look like branches.

How sticky are our objects? One of the reawakenings of our present moment is the slow (or fast) recognition that our everyday objects are, in fact, never quite severed from much larger circuits, webs, and ecosystems. They are sticky. They attach themselves to other objects and become quickly bound by gravitational fields, networks, tendrils, and pathways—lifeways. The work in this show imagines that objecthood encompasses all these definitions. These sticky objects make some claim to autonomy while simultaneously acknowledging their place within larger ecological, geometric, technological, and historical landscapes.

How much are we affected by, or affect the environment we inhabit? Does a tree grow out of the earth, made almost of the same stuff, or does it exist as a distinct entity, moving through the soil but still animated by a different life force? What is it that organizes the world? Is it the underlying principles of geometry? Is it the material substrate? The agency of life? These stick objects propose that vitality might remain alongside precise dimensionality and abstract geometric operations.

A stick is no longer a tree.

A stick is a tree.

Joshua G. Stein is the founder of Radical Craft, a Los Angeles-based studio that advances an experimental design practice rooted in history, archaeology, and craft. He is also the co-director of the Data Clay Network, a forum exploring digital techniques applied to ceramic materials, and a Professor of Architecture at Woodbury University, Los Angeles.

Points of Connection by Del Harrow and Yonatan Hopp was on view between April 4 and May 3, 2025, at Sculpture Space NYC – Center for Ceramic Art, New York.

Subscribe to Ceramics Now to read similar articles, essays, reviews and critical reflections on contemporary ceramics. Subscriptions help us feature a wider range of voices, perspectives, and expertise in the ceramics community.

Photos courtesy of Sculpture Space NYC