Jay Kvapil is a California artist whose work has been shown at the Renwick Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; the Oakland Museum; Scripps College; the San Jose Museum of Art; San Francisco State University; the Taipei Fine Arts Museum; and numerous other national and international exhibitions. Formerly represented by the Dorothy Weiss Gallery in San Francisco, the Joanne Rapp Gallery in Scottsdale, Arizona, and Couturier Gallery, Los Angeles, he is currently represented by Galerie LeFebvre et Fils, Paris; Mindy Solomon Gallery, Miami; and Diane Rosenstein Gallery, Los Angeles.

Upon finishing undergraduate studies, Jay studied tea ceremony ceramics in Japan at the Takatori Seizan Pottery on the island of Kyushu in Southern Japan in 1974-75. After returning to the United States, he received both his MA and MFA from San Jose State University where he also served as Conference Director for the National Council for Education in the Ceramic Arts Conference in San Jose, 1982.

Now Professor Emeritus, he served numerous roles at California State University Long Beach over a period of 36 years, including Director of the School of Art, Associate Dean, and Interim Dean for the College of the Arts; and as Dean of the College of Arts, Media, and Communication at CSU Northridge. At the national level, he served as Board Member, Treasurer, and Member of the Commission on Accreditation of the National Association of Schools of Art and Design.

Visit Jay Kvapil’s Instagram page.

Artist profile created with the participation of Mindy Solomon Gallery, Miami.

Featured work

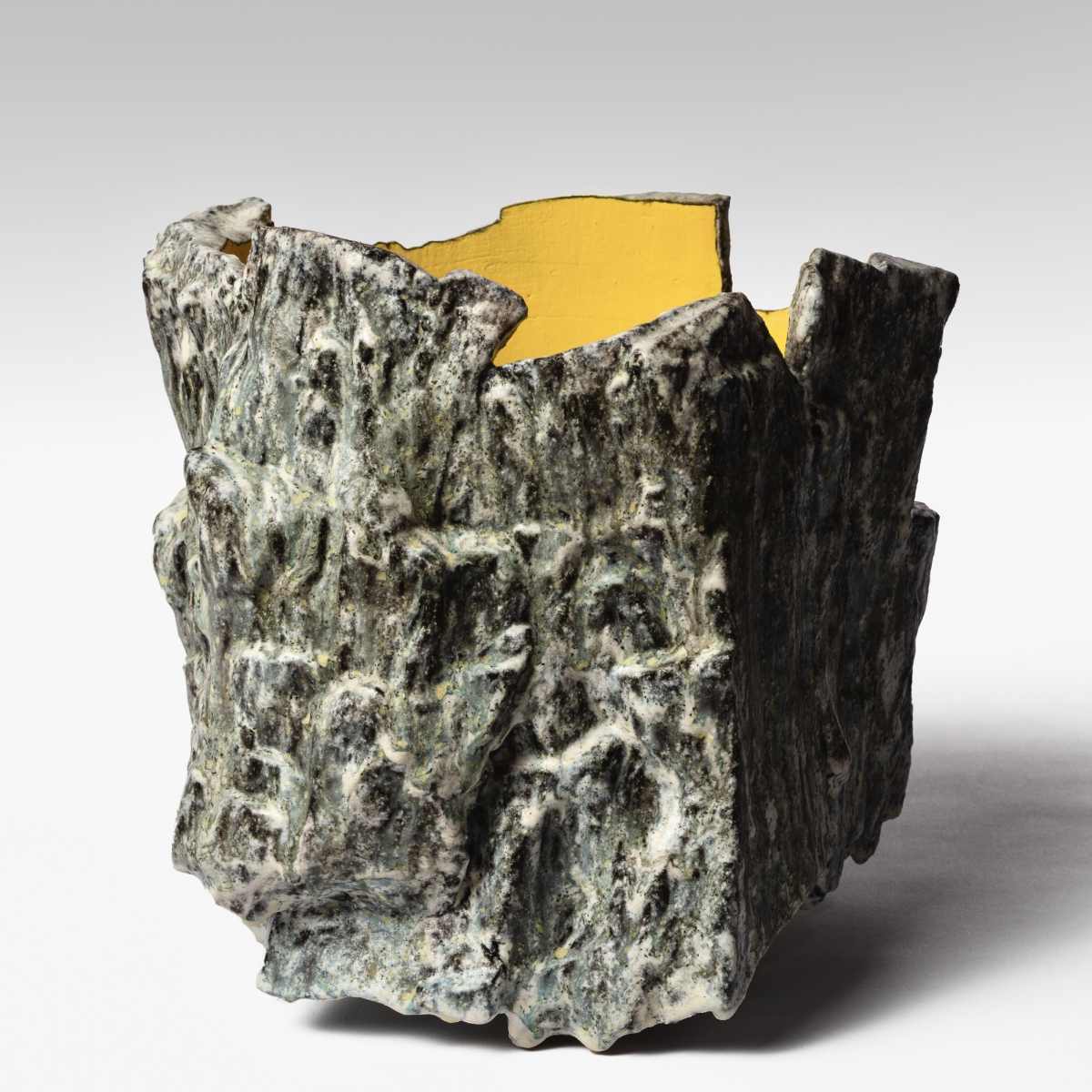

Floe Series, 2021-2022

The work has no meaning. There is only meaning if the viewer decides there is meaning, which means there are only potential meanings, no universal meaning. If there is meaning at all, there are potentially as many meanings as there are viewers.

Thus, I am always hesitant to write about my own work. It’s something about explaining something before the viewer has the chance to view the actual pieces, before hearing from the pieces themselves what they have to say. I imagine myself standing in front of the work talking to a group of people who are looking at the pieces and me telling them what they should see. (“Should,” of course, is a very suspicious word.) In my perfect world, the viewer would spend some time with the work and then ask me some questions.

My work in recent years has mostly been highly-glazed pictorial ceramic vessels evoking semi-abstracted broadly-imagined landscapes. At first look the Floe Series might seem to be a big departure from those earlier vessels, but in fact, the Floe Series deals with many of the same ideas: still ceramic vessels, still highly glazed, still landscapes – but the imaginary landscapes on the surface of earlier vessels have now become invented stones that are themselves landscapes. Form and surface merge. The pictorial elements and the forms are one, just the way a small stone might reflect the entire landscape from which it was plucked.

Landscapes in all their forms, broad or narrow, infinite or infinitesimal, all amaze. How can one dare to think a landscape in all its majesty can be captured by a painting, a photograph, a sculpture, or a vessel? It’s daunting to be overwhelmed by a landscape and then try to make something that reflects upon it. Seems like a fool’s errand. But I do think ceramics is a perfect medium for attempting such a feat. For ceramics can be the practice of breaking down a landscape–I mean a literal landscape, rocks and dirt–and make something with them. It seems a little weird, doesn’t it, to take from the landscape and then remake it into another landscape?

I am quite conscious that alchemy, is what we as ceramic artists do — take dirt and finely ground rocks and make them into something new again. When I think about it, all the materials I use–both clays and glaze ingredients–are mined all over the world, and then are refined and packaged for dispersal throughout the planet. We take these “natural” materials and remake them into new forms, and then bake (or fire) them to create hard, strong, and impermeable things. Dirt to gold, alchemy.

Regarding the process for the Floe Series, I start with plaster molds I take from selected surfaces of rocks that I have collected, then make detailed clay slabs from those molds, and facet by facet, “stitch” them together to make new “rocks” that are double or triple-walled, and that take the rough form of vessels. The process is analogous to computer “stitching” of photos. I suppose this could all be done with software and a 3-d printer, but that just doesn’t work for the way I think, and the way and I see. For now, all the pieces are still vessels, for the rich history to which I speak.

The Floe Series got its title from my own reflections upon, and relish of, icebergs, ice floes, and the like. They are incredibly beautiful impermanent landscapes, but are also humongous objects that defy scale, and that change by the hour, and then disappear. I could have titled the series “Reflections on Impermanent Landscapes.” But then again, aren’t all landscapes impermanent anyway?

Jay Kvapil, September 2022