By Marc Leuthold

“Crashing Ceramics,” a multi-media, installation-based group exhibition curated by Mr. Feng Boyi, Ms. Li Yifei, and Mr. Gao Wenjian, featured 30 avant-garde artists at the Taoxichuan Longquan Wangou Museum in China. Longquan is the site of extraordinary celadons dating back to the Song Dynasty, a thousand years ago.

Exhibiting artists are based in China unless otherwise noted: Chen Xiaodan, Clarissa Falco of Italy, Elysia Athanatos of Cyprus, Feng Feng, Gan Haoyu, Geng Xue, Hong Hao, Juju Wang, Li Binyuan, Jaffa Lam, Liu Jianhua, Liu Xi, Lu Bin, Marc Leuthold of USA and CH, Ryan Mitchell of USA, Patty Wouters of Belgium, Richard Garrett Masterson of USA, Song Zhifeng, Sun Yue, Susan Kooi of Holland, Tobias Kvendseth of Norway, Wongil Jeon of Korea, Xiao Li, Xie Wendi, Yang Xinguang, Walter Yu, Kerry Yang, Stella Zhang of USA, Zhou Hehe, Zhou Jie.

The lead curator of “Crashing Ceramics,” Mr. Feng Boyi, is a conceptual curator who is interested in material-based artists. In the West, such artists are often referred to as “craft” artists—a term usually dismissed in the broader art world. Mr. Feng does not embrace media-based prejudice, and as a close friend and collaborator of artist Ai Weiwei, recognizes that art knows no boundaries. Mr. Feng’s early career included groundbreaking essays about Chinese contemporary art interwoven with Ai Weiwei’s political philosophy. In Shanghai in 2000, he curated the exhibition titled “Fuck Off,” which was known in China as “Uncooperative Attitude”. The exhibition was closed almost immediately by the government. Currently, Mr. Feng directs the He-Xiangning Museum in Shenzhen, and next year will oversee some of the projects that the International Academy of Ceramics will host at its meeting in Jingdezhen.

In Feng Boyi’s “Crashing Ceramics” curatorial statement, he invokes the term Pengci, invented by late Qing Dynasty (ca. 1900) Beijing residents who would clutch a delicate porcelain vessel while jaywalking in such a careless fashion that drivers would accidentally collide with and destroy the porcelain, thus requiring a financial settlement. Mr. Feng believes that Pengci is a useful metaphor for the “Crashing Ceramics” artists who are routinely “breaking through the restrictions and limitations imposed by traditional ceramics.” Mr. Feng, using the concept of Pengci, ably tables the endless “art vs. craft” debate.

This complex exhibition project resulted in mostly solo installations by thirty artists. As such, the exhibit occupied the entire two-story Museum. Such an enormous undertaking would not have been possible without the assistance of Mr. Feng’s curators, Li Yifei, Gao Wenjian, and other staff.

As a finishing touch, Mr. Feng invited one of his frequent curatorial collaborators, Bjorn Follevaag of Norway, as a keynote guest during elaborate opening ceremonies.

Almost all of the artists incorporated Longquan celadon ceramics within their installations or sculptures. This in itself is revolutionary. It is hard to imagine an exhibition of avant-garde art that incorporates the renowned Chinese Longquan ceramics tradition, famous for its rich blue and green celadons. About a 1000 years ago, Longquan was a top producer of prized ceramics, the best of which were created for the Imperial Court. The ancient forms were clean and precise with the distinctive blue glazes. There was little surface decoration and the purity of form was almost modern in feeling. These works were mostly functional and finely potted. Subsequent dynasties saw a decline in refinement with bulkier forms. The decline continued until the rise of Chairman Mao after 1949, whose government supported and funded a revival of Longquan ceramics. These mid-twentieth-century Chinese artists sought to recreate past glories and surpass them within a traditional artistic vocabulary. In recent years, universities have established outposts in Longquan – elaborate, lavish studios and galleries with gardens and production facilities. Recently, Taoxichuan established a large facility by renovating an old factory complex and constructing key new facilities. Taoxichuan is a corporation that leverages government support and attracts investors, inviting Chinese and international artists to create art using local clays and glazes in Jingdezhen and Longquan.

The exhibition featured two groups of creatives. There were artists who had not worked with ceramics, and these artists came to Longquan beginning in late 2024 to create artwork at Taoxichuan Longquan. A second group of artists has worked with ceramics for decades. Many of these are contemporary (not traditional), celebrated Chinese artists.

For the exhibit, artists were invited to experiment, surpass previous works in scope and scale, and, at times, to collide with one another and with their own creations in order to innovate in a traditional medium. Innovation has been a key driver of China’s modern development and remains a focus of Chinese society. This is more obvious in manufacturing and technology (electric cars), but Chinese leaders believe that innovation is not a gated community restricted to the business world. Innovation is a wholistic goal encompassing all of society including the arts. Projects like “Crashing Ceramics” receive support from both government and private sources. The United States also once embraced this approach. For example, during the 1950s Cold War, the United States quietly supported Abstract Expressionist painting as a uniquely American cultural signature. During the Cold War competition with the Soviet and Maoist systems, the American government funded artists like Jackson Pollock by funneling Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) funds via the (William S.) Paley Foundation and the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. These American organizations and their patrons commissioned, purchased, and exhibited bold, daring large paintings. All of this is to demonstrate the supposed superiority of the American free-enterprise system. How else could impoverished artists like the Abstract Expressionists have created paintings that sometimes were 6 meters high and 10 meters wide? While those days in the United States are long gone, China recognizes the power of culture within their nationwide rejuvenation project. As a result, it has embraced iconoclastic curators like Mr. Feng. While Ai Weiwei was, of course, not included in this exhibit (remember, many of his works, such as the Tate Museum’s sunflower seed installation and his Coca-Cola vessels, were ceramic-based), other masters were.

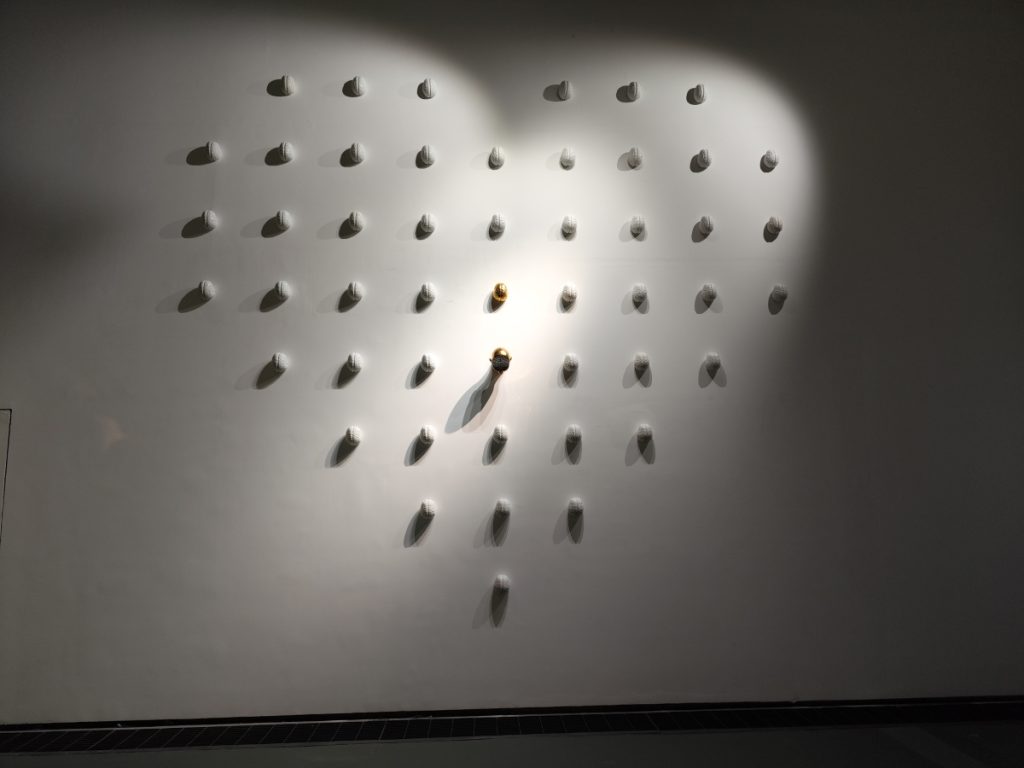

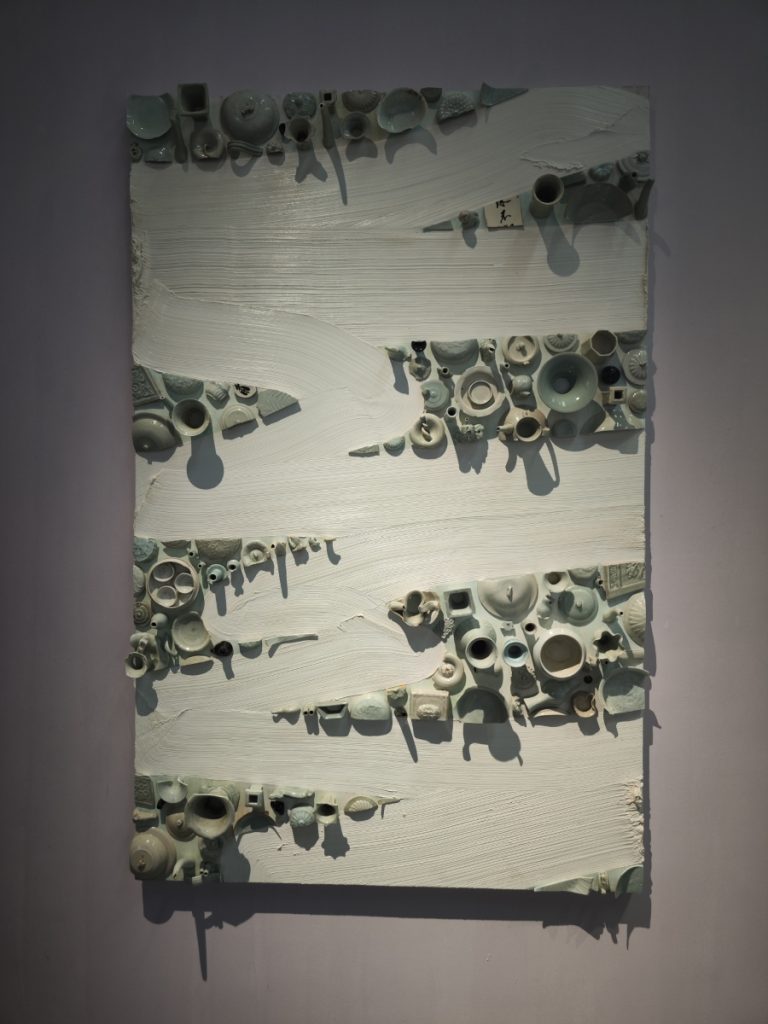

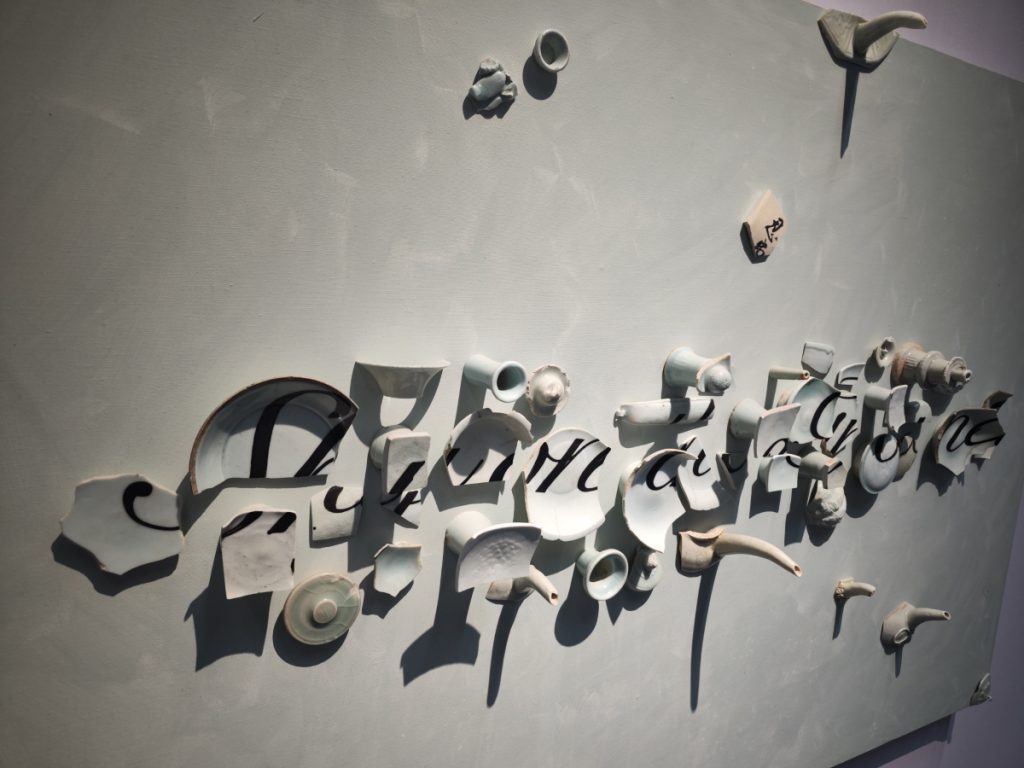

Near the Museum entrance, the widely admired artist, Mr. Feng Feng, had installed a piece consisting of many ceramic brains mounted on the wall. The ensemble of dozens of brains was shaped like a heart, measuring 4 meters in height and width. At the center was a golden head and a golden brain. Mr. Feng Feng celebrates emotional/empathic intelligence – a reminder of the importance of love, something easily forgotten in a material and technologically driven society. Next to Mr. Feng’s artwork, another world-famous Chinese artist, Li Binyuan, presented “Rumor,” a ceramic tongue pierced by an arrow that succinctly addresses censorship, both by government and society. In China, censorship is only formal, imposed by the government. In contrast, in the West, we are free to speak our minds, but we usually don’t because many topics and words are considered taboo. In the digital realm, words have become an even more lethal weapon. Nearby, Mr. Liu Jianhua exhibited brightly pigmented, quickly created, porcelain globs, titled “Color”. The unselfconscious simplicity of these forms is meant to correspond to a spiritual purity. Mr. Liu exhibited art at the Venice Biennale in 2017, and his work has been collected by Tate Modern, MoMA, and the Guggenheim Museum. Rounding out these Chinese superstar artists was Mr. Hong Hao. In his work, Mr. Hong has incorporated Song dynasty Longquan shards, relics of imperial-grade vessels within abstract paintings – a series titled, “Realm of Objects”. Rich impasto paint in light muted colors, surround and embrace the shards. One of these paintings is a mandala, and another is like a Japanese Zen garden. Instead of gravel, rich furrowed impasto brushstrokes surround and draw attention to the precious ancient ceramics. The functional ceramic shards (broken high-quality wares) have thus been transformed into paintings – the apogee of the visual arts as established long ago by the French Royal Academy. In this way, Mr. Hong has elegantly subverted the Western prejudice against ceramics and crafts – long considered a lowly medium, not to be exhibited with paintings at the Academy.

Further into the Museum galleries, Ms. Liu Xi presented a masterful installation of black and gold castings, suggesting remnants of the David. The David here is deconstructed and blackened, yet also gilded with gold luster. Near Ms. Liu’s work, Stella Zhang, a Chinese-born artist residing in California, created a poetic installation of organic forms that embodies an Asian aesthetic sensibility within Western concepts of contemporary art. Another famous Chinese conceptual artist is Xiaodan, an artist who recognizes no limits in her practice. For years, she has created and exhibited huge and small ceramic bones and gestural forms encrusted with flowers. Ms. Xiaodan has created installations and videos with a haunting quality in which she explores elemental themes of death and resurrection. In this exhibition, her installation “Build and Destroy” consists of two large racks filled with brick-shaped vessels containing bones. Xiaodan creates visual interest through intense repetition, scale, and the evidence of fire and burning, referencing cremation, the afterlife, and enlightenment. Her work is abstract enough not to be didactic or limited to one interpretation – a temptation that is usually best resisted.

Yet another famous artist, Ms. Geng Xue, has spent her entire adult life at the Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA) in Beijing—the Chinese equivalent of the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in Germany. I met her as she was graduating from CAFA. As a graduating student over 15 years ago, she displayed a menagerie of hundreds of ceramic figures engaged in daily Chinese activities. This narrative diorama was abstracted in such a manner as to resemble a Chinese painting in three dimensions. Ceramics in the Sculpture Department at CAFA has long played an important role, thanks to the leadership of former Dean Lv Pinchang, now the President of Jingdezhen University, which is the largest and oldest ceramic university in China. It is rumored that a Swiss collector purchased Ms. Geng’s entire menagerie of figures for more than 1,000,000 RMB, and that Geng wisely bought an apartment and studio in Beijing, thus securing her future. Now, she teaches at CAFA and has branched out to create videos. Geng’s videos often touch on the notion of ceramics as a primordial medium. Her video at Longquan has a mythological undertone, with a narrative featuring a protagonist who serves as the divine creator, bringing life to the inanimate clay.

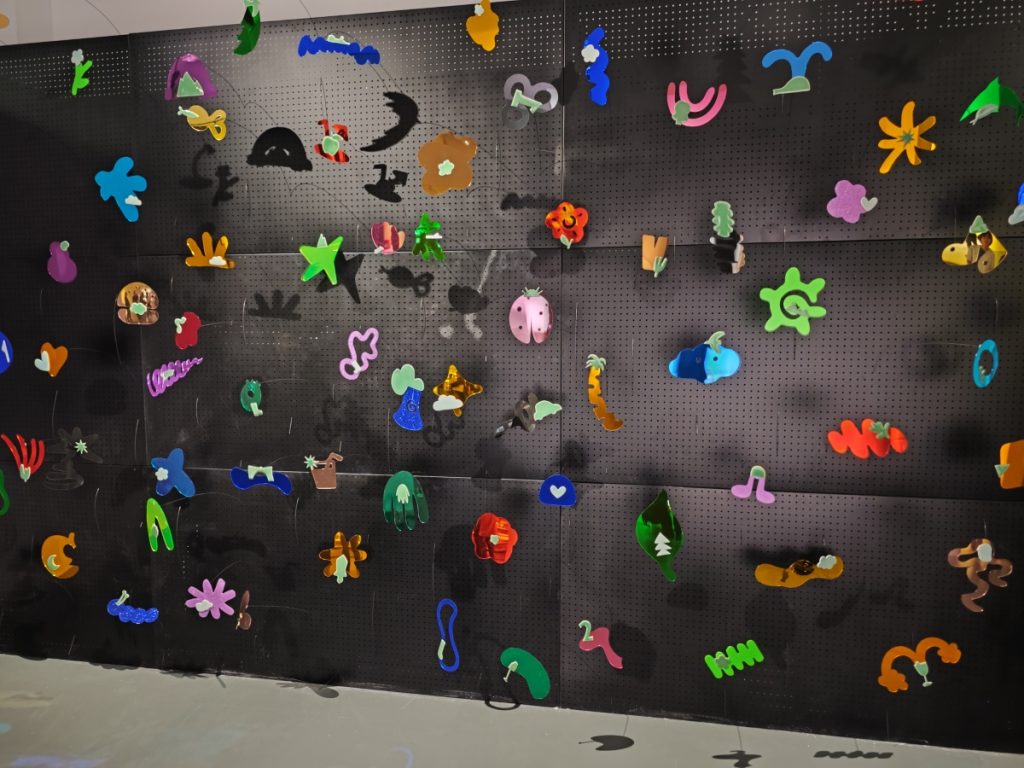

In their curatorial statement, Mr. Feng and his curatorial team mention that, in addition to famed mature Chinese artists, they also prioritized young artists. One of the most promising is Ms. Sun Yum, a former student of Tsinghua University Professor Baiming. Sun presented an installation of unfired, life-like flowers made in the style of artists from Dehua, a town renowned for its translucent, jade-like clay. Hovering above the ceramics in a terrarium-like tube were lacy ferns whose water drippings would erode the clay in the course of a six-month-long exhibition. Having left China, I was unable to witness this evolution, but her work set up a narrative that lives in our minds as we imagine the erosion and disintegration of her fine work. Another young artist, Ms. Juju Wang, presented a wall montage, “Ethereal Symphony: Between Realms,” of glittering metallic shapes, each with a small celadon ceramic appliqué. These forms project from the wall on thin wires. A nearby fan caused the glittering shapes to flutter and dance—a lively, dynamic installation. Interestingly, this artist, a Chinese-American, was wooed back to China and has been officially recognized as one of the top 100 cultural creatives in China by a government that strives to lure Chinese ethnic groups back home. Another emerging artist, Mr. Yang Xinguang, created a series of abstract forms richly glazed with Longquan light blue celadon. All these forms were punctuated by wooden branches that were carved and inserted into the clay forms. Poetically arranged and wholly abstract, the forms were like a calligraphic Haiku presented on a large, low horizontal plinth. Another emerging artist, Ms. Zhou Hehe, presented a teepee of large burnt wooden beams pierced by dozens of ceramic spikes in a darkened room. This powerful sculpture, whose linear elements all pointed skyward, was a strong contrast to the nearby child-like, deskilled landscapes, vessels, and creatures presented by Dutch artist Susan Kooi. Another young Chinese artist, Ms. Jaffa Lam, worked with clay to capture the texture of the fine old trees that surround the buildings of the Taoqiquan Longquan campus. She did so by moulding clay on the bark while having a photographer capture the process. In the exhibition, she showcased her ceramics and photographs documenting her creation process.

Artists from all over the world were represented in the exhibition, and refreshingly, there were new faces included. In early Spring, Mr. Feng, Ms. Yi, and Mr. Gao visited the Taoxichuan Longquan Wangou creation village to meet with artists who had been invited to create artwork for the Crashing Ceramics exhibition. Not all of the artists working at Longquan Wanghou had been invited to exhibit. But Mr. Feng and his team agreed to visit ALL the artists’ studios and chose to include all the artists. In this manner, Patty Wouters, Elysia Athanatos, and Clarissa Falco joined the exhibition. This was especially felicitous in the case of Ms. Athanatos. Athanatos created enormous thrown porcelain forms that did not survive the creation process intact. As such, she hung about 50 shards in the air that appear to be crashing towards the cement floor of the gallery. In the dozens of Chinese articles about the exhibit, this was often included as a signature sculpture of the exhibition. It seemed to epitomize the Pengci anecdote that underpins the curators’ exhibition concept. Athanatos proved to be a master of poetic adaptation in the face of calamity.

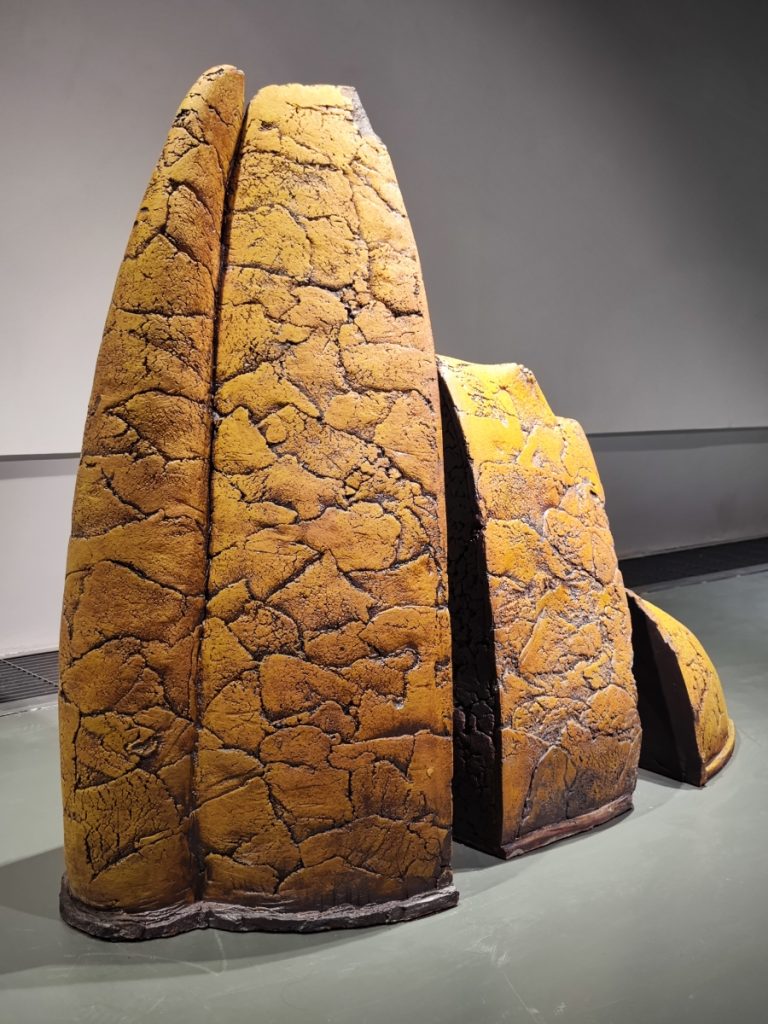

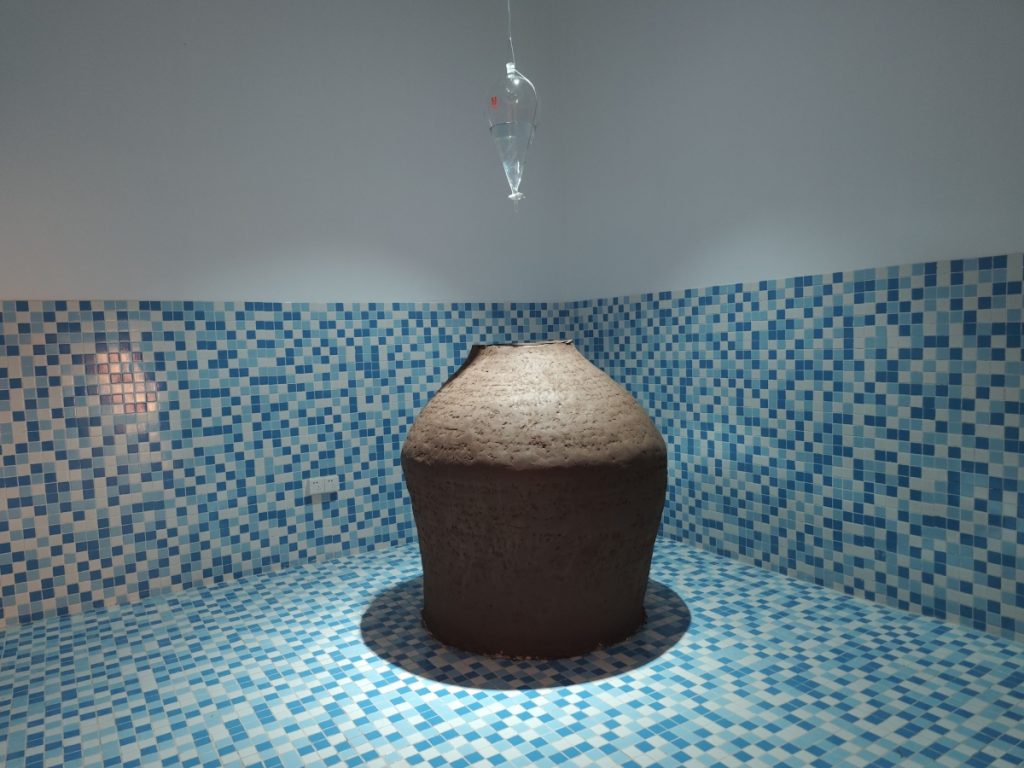

As one climbs the stairs to the second floor of the exhibition, the arresting work of Richard Garrett Masterson of California is immediately visible. The sculptures consisted of two press-molded conjoined forms. What is startling about this work is the mutual tension the artist created by the proximity of a second form that appears to just barely balance on a larger monolith. The forms are often bright ochres or terracotta, or dark gray. The artist eschewed the ubiquitous Longquan palette of blue glazes. Nearby, Walter Yu created a miniature village of small traditional Chinese buildings with light and sound. Patty Wouters created a circle of wafer-thin, translucent, lily-pad-like leaves balancing on 30 cm tall stems. Next to Wouters’ installation, artist Mr. Song Zhifeng, who studied art in Germany, displayed his work on the gallery floor. After creating a fascinating, thick, extruded architectonic form that was fired too quickly, the artist pivoted abruptly and presented thin, blue, irregularly shaped pieces of glazed tiles laid on the floor, which referenced a window. Chinese, Japan-based artist Ms. Xiao Li, like Ms. Sun, created a time-based, evolving work. In a small enclosed space whose walls were covered with Longquan blue tiles, Li built a large coiled pot. Hovering above the unfired clay, a clear pouring vessel drips water on the clay – presumably creating a ruin for later viewers.

In a similar vein, Mr. Lubin, a professor at Nanjing University and a curator in next year’s IAC activities in Jingdezhen, presented a phalanx of traditional Longquan forms that were designed to begin to self-destruct after a couple of days. The resulting wreckage evoked the ever-present Longquan shards encountered in the shops, museums, and on the ground – the legacy of a thousand years of ceramic creation and failure. Nearby, Mr. Gan Haoyu exhibited a machine that jerks, jolts, and sputters while creating ceramic forms much like a mud dauber creates its home on a wall. Using brilliant orange clay, the elaborate, noisy Tingley-like machine, garnished with primitively potted vessels, made an eerie noise heard throughout the galleries. Artist, Mr. Wongil Jeon from Korea, is a painter who has never worked with ceramics before. After making a series of beautiful egg-like spherical forms of varying sizes, he found that many of the larger ones failed in the kiln. In response, he painstakingly made similar forms out of cut paper. Accompanying the linear display of these spheroid forms was a video in which he used his body language to outline similar forms by arcing his arms high over his head and around his body, possibly referencing Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. Nearby, Ryan Michell, an American who has lived in Jingdezhen for decades, exhibited large, roughly formed, asymmetrical vessels that recall the mountainous landscape often depicted in classical Chinese paintings. His pastel palette of non-Longquan glazes is highly varied, quietly echoing and enhancing the forms. The satiny matte surface was a felicitous choice.

One of the most significant artists in the exhibition was Tobias Kvendseth of Norway, a protege of the exhibition’s guest of honor, Bjørn Follevaag. Mr. Kvendseth, still in his late twenties, used his time in Longquan to create a series of reductivist forms that allude to tools and weapons. These black and white forms were presented on four light tables. The dramatic, literally electric, presentation was possibly inspired by ideation surrounding violence in his culture towards those who embrace alternative lifestyles.

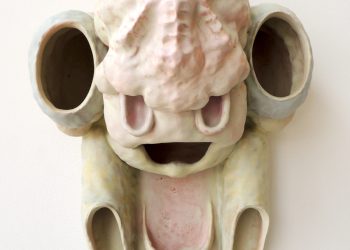

Perhaps the most unusual presentation was created by Clarissa Falco of Italy. Ms. Falco, during her time in the Taoxichuan Longquan Wangou art village, created a series of masks, claws, and jangling anklets from clay. On the opening day of the exhibition, she wore these ceramic forms and offered a performance directly after the opening speeches. As she moved about in yogic fashion, the sounds of her percussive ceramics punctuated her movements. Dousing herself with an urn full of water, followed by another containing sand, she became an encrusted, motile sculpture herself, finally offering some of her ceramic ornaments to the fascinated viewers.

Article author, Marc Leuthold, also created an installation for the exhibition. During his time making art in Longquan, Leuthold invited everyone to his studio to feel the texture of Longquan clay in their hands, which he subsequently glazed with Longquan celadons. Five hundred fifty-seven of these squeezed clay forms were suspended from the Museum ceiling, creating a path towards a pedestal upon which sat a dozen or so circular clay mandalas. Viewers inadvertently collided with the suspended glazed forms, causing them to chime. In the Taoist tradition, the ringing of bells and the playing of music hold special significance, as they serve as both instruments in the temple and are a medium to evoke reverence for the spiritual.

Feng Boyi, Li Yifei, and Gao Wenjian – with an army of staff support, worked tirelessly for about ten days organizing and installing thirty separate artistic visions into a cohesive exhibition, a multi-media visual experiment that may help redefine ceramics as an expressive artistic medium – a medium that transcends and simultaneously embraces modern, traditional, and conceptual themes in art. The curators hope their “fundamental curatorial purpose” of offering viewers a “deeper understanding of the metaphysical contours of contemporary ceramic arts” will be fully embraced. Judging from the plethora of visitors and the numerous Chinese articles, videos, and programs about the exhibition, they succeeded.

Marc Leuthold is an artist who has been invited to exhibit and create art worldwide. Leuthold’s artwork has been exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and PS1 MoMA, both in New York City. Leuthold has served as a Professor at the State University of New York, Princeton University, Parsons School of Design, and Shanghai Institute of Visual Arts.

“Crashing Ceramics” was on view between May 5 and October 1, 2025, at the Taoxichuan Longquan Wangou Museum in China.

Subscribe to Ceramics Now to read similar articles, essays, reviews and critical reflections on contemporary ceramics. Subscriptions enable us to feature a wider range of voices, perspectives, and expertise within the ceramics community.