By Debra Sloan

Essay on Written in Clay, Ceramics from the John David Lawrence Collection, at the Vancouver Art Gallery. On the Traditional Coast Salish Lands including the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish) and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations.

The exhibition, Written in Clay, Ceramics from the Collection of John David Lawrence1, being held at the Vancouver Art Gallery (VAG), in Vancouver, British Columbia (BC), is devoted entirely to the studio ceramics of this region. The collector, John David Lawrence was drawn into the world of ceramics over twenty-five years ago while managing his glittering warren of goods and goodies in his store, DODA ANTIQUES, in the downtown core of Vancouver. As BC ceramics started to accumulate in his shop, refugees from craft fairs and estates, Lawrence began to succumb to their allure. He became hooked on identifying the makers, as any good collector would, and familiarized himself with artists’ choices of clay, glaze and form, and, importantly, he always collected any associated stories. Inevitably Lawrence began to amass his own private collection, which gradually migrated from shop to home, and over time he has happily conceded much of his living space to gleaming ranks, rows, and towers of pottery. He is adamant that all works remain on display.

Collectors are the stewards of object -provenance, they metamorphose into creatures of object-love, and become entangled with object-stories. They safeguard those things, which by virtue of being collected, have become aesthetic purveyors of the time and place of their origins. Ultimately, what determines the validity of any collection is the collector’s ability to sense and recognize the merit of what is within their reach. In the John David Lawrence Collection, of several thousand ceramic works, every piece has its own place, and every piece has its own story, and the stories matter. In British Columbia, studio ceramics did not organically evolve from existing traditions, but rather, from the 1920s were rapidly introduced through the agencies of both immigration and imported knowledge. The repercussion of the ceramic practice not being rooted in this place is that our cultural institutions have been slow to become engaged and informed, and with few significant regional ceramics held in public institutions, works are still being preserved in private collections, and the anecdotal knowledge is being stashed in personal recollections. To paraphrase Lawrence in his conversation with Michael Prokopow, in the publication, The Place of Objects…2 He said that the legacy of his collection includes himself, meaning his memory.

Sometimes Lawrence is in contact with the makers, at other times he is chasing BC legends, like Ebring, Kakinuma, Davis, Ross, Hughye, Ngan, or Reeve. The act of collection has turned Lawrence into a recognized BC ceramic expert, and he frequently loans ceramics to public galleries across Canada. One such exhibition was for the VAG’s 2020 Modern in the Making, Post-War Craft and Design of British Columbia3, for which he loaned 40 works. During the selections the VAG gallerists became familiar with his collection, and this led to Written in Clay. For the purposes of this exhibition Lawrence, and curator, Diana Freundi chose 186 works, made by forty different BC artists. His vast collection is tipped heavily to the 20th Century, however, the works displayed do range from 1924 – 2014. Lawrence has a great respect for functional pottery and is very sensitive to reduction-fired glaze. To reflect his preferences of pot and glaze, the bulk of the exhibition is made up of gas or wood fired functional ware, with only a small percentage of figural or purely expressive works.

The curation for Written in Clay borrows from a 1972 show of John Reeve’s ceramics, one of four solo exhibitions of BC ceramics held at the VAG during the 1970s. Reeve’s pottery was displayed on wooden planking, supported on cement breezeblocks, intended to suggest potters’ ware boards. This style of installation has been echoed in Written in Clay. It is also reminiscent of the ubiquitous breezeblock/pine board shelving, acting as display units at the craft fairs in the 1960s/70s, the fastest, cheapest (and heaviest) method to make a display. In this exhibition there are three ‘islands’ located in the centre of the gallery, each with tiered platforms, again supported by the breezeblocks. The deliberate placement of the ‘island’ pots successfully amplifies the diversity of regional practices. The intervals between disparate neighbours, using distance and visual contrast spark dynamic interplays, while still allowing enough air around each piece to also see it as a distinct entity. This enables the viewer to see that every work is characterized by diverse choices of form, colour, embellishment and intention, as well as by various clay, glaze, and firing technologies. The only information supplied for the island ceramics are titles, dates and artist names, with the overarching message being how distinct and variable every ceramic practice is.

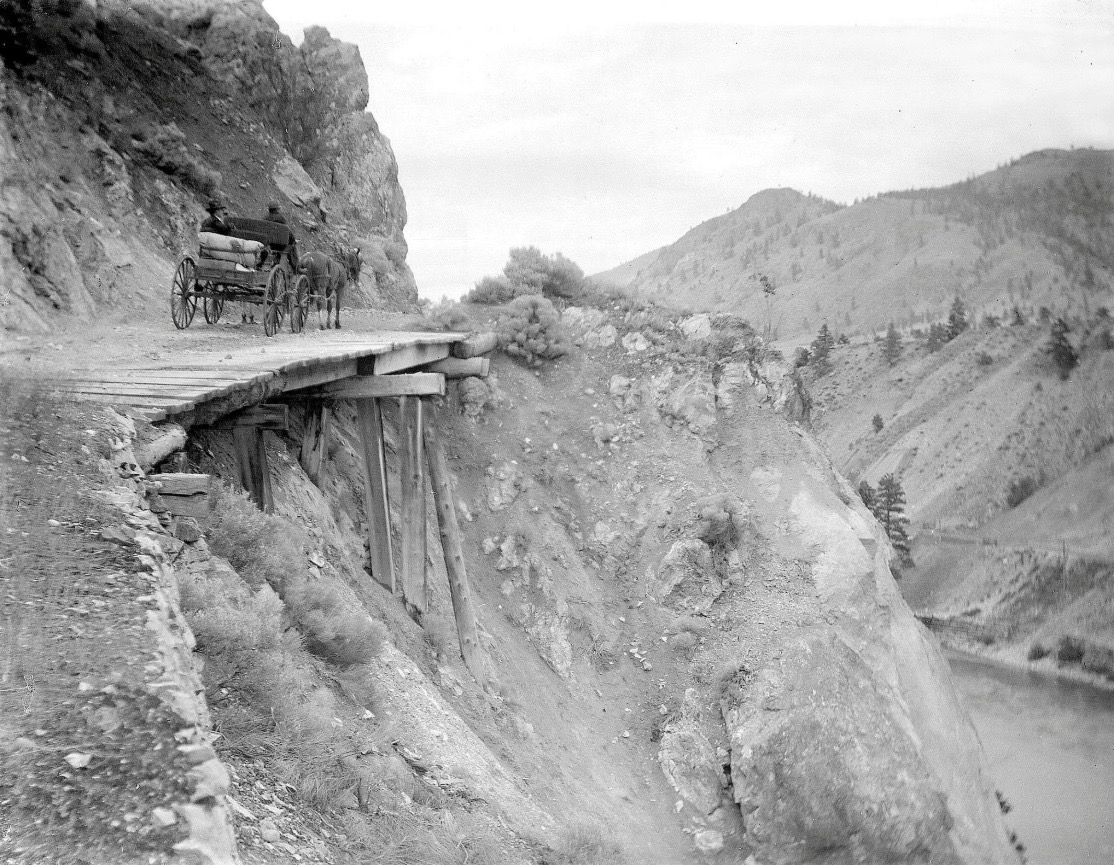

Around the periphery of the gallery are eight spotlight displays featuring the artists that Lawrence was able to collect in depth. These displays have been managed differently, using profiles of the work to show off form and glaze, with a short precis on each artist. The earliest studio potter in BC, Axel Ebring, had been trained in Sweden by his father and grandfather. He arrived BC in the late 1900s, and by the mid 1920s established his first pottery in the interior of BC. It is hard to convey to those outside of British Columbia, the type of terrain, the isolation, and the challenges this location would have presented in that era. There were no commercial or traditional ceramic resources whatsoever, and a drive to Vancouver, the closest sizable city, 450 kilometers away, in a cart or car, would have taken many hours, even days, hampered by broken wheels or flat tires, in unpredictable weathers, and on questionable unpaved, and scary mountain roads. Ebring had to find and manufacture all of his own materials and tools, so he located his workshop near clay and mineral deposits. Another notable aspect of his practice is that he was well established long before the pervasive Leach/Mingei and Modernist influences, especially those from post WWII to the 1970s, had infiltrated much of the studio pottery of the Western world. Consequently, his handsome, vintage forms and lustrous glazes, many of which are lead based, do stand out. In contrast, the pottery of two other spotlight artists, Ontario born, John Reeve, and British Columbian, Charmian Johnson, both Leach apprentices and acolytes, are all about interpretations of Leach/Mingei. The pottery of Wayne Ngan, who arrived in Canada at age 13, elegantly moves through an intersection of influences – Asian, Leach /Mingei, and Modernism. Laura Wee Láy Láq, one of BC’s earliest Indigenous ceramic artists, of Stó:lo (Coast Salish) and Wuikinuxv (Oweekeno) ancestry, focussed on organic form, using coiling, burnishing and pit firing to beautiful and meaningful effect. Albertan, Walter Dexter, who trained in the prairies with Luke Lindoe, and then in Sweden, and Vancouverite, Kathleen Hamilton, both demonstrate the influences of modernist rigour and Scandinavian design. Thomas Takamitsu Kakinuma is represented by his much -loved animal figures. Kakinuma arrived from Japan, in 1937, but it was in the 1950s he acquired his ceramic skills, in both Ontario and at the Ceramic Huts at the University of British Columbia.

Of these spotlight artists, Johnson, Hamilton, and Wee Láy Láq, are the only artists born in BC. Other than Ebring’s work, which is founded on a village tradition, all of the other spotlight artists reveal 20th Century influences that have been delivered to BC. Of the 32 island artists represented, 11 were born in BC, and breaking that down further, almost all of the more senior artists in the exhibition were born elsewhere in Canada, or worldwide. This is the aforementioned characteristic of BC ceramics – its evolution having transpired through external influences, rather than a natural progression led by regional tradition. The dynamic growth of BC’s ceramic arts reflects the extraordinary transformations of the 20th Century around culture and technology, accelerated by the increasing speed of communications. When Belgian potter, Robert Weghsteen, immigrated to Canada in the mid 1950s, he chose to ship his entire studio, equipment and materials, by freighter to Vancouver, rather than deal with potential deficiencies in BC. In a 1989 essay about BC studio ceramics, curator, Glenn Alison and artist, James Thornsbury professed that they could not find evidence of distinct or prevalent BC ceramic traditions. Instead, they came to the conclusion that the strongest work was …”that of isolated, idiosyncratic, individualistic, personal, independent production…that resists classification, or critical scrutiny in any combinative process.” These maverick attributes persist, even though information and influences are disseminated worldwide, the regional perception of being physically isolated and individualistic remains, and is evident in the diversity of the ceramic practices as seen in the exhibition.

One impact of Lawrence’s ceramic collection is that it became a primary source for the nascent BC Ceramics Marks Registry, an online record of BC ceramic marks and artist profiles being developed by the author, with the support of the Craft Council of BC. With Lawrence’s help, and that of Canadian craft historian, Allan Collier, the provenance around the first centenary of studio ceramics in BC has been protected. It is our great hope that by creating this provenance institutional interest will follow and lead to a material arts establishment. At this time the non-Indigenous material arts are without any formal agency protecting their collections and archives. The Indigenous arts, the foundational arts in BC, are splendidly housed in the University of British Columbia’s Museum of Anthropology. For decades the two genres have travelled in parallel trajectories, until, at long last, they were brought together in two seminal exhibitions, the 2020/21 Modern in the Making Post-War Craft and Design of British Columbia exhibition, and the Craft Council of BC’s 2020 Personal and Material Geographies4. It is hoped that this long overdue rendezvous may awaken more advocacy. Most countries, and many Canadian provinces, do have specialized galleries for their material arts and cultures. In BC our history rests tentatively on private collectors, like Lawrence. For all of these reasons the documentation and curation around the Written in Clay exhibition, has been exceedingly relevant for the material arts culture in BC. Accompanying the exhibition is the beautifully illustrated publication, The Place of Objects, the John David Lawrence Collection. Editors, Stephanie Rebick and Michael Prokopow, collected 36 essays from artists, collectors, and curators, reflecting on the social and cultural impacts of collection, as well as delving into portrayals of Lawrence’s other extraordinary assemblages.

Written in Clay, Ceramics from the John David Lawrence Collection is a breakthrough exhibition, marking the first ceramic exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery in 36 years, since the 1979 showing of the celebrated BC potter, Wayne Ngan. Lawrence’s own maverick imersion into the cultural ecosystem of his neighbourhood, and his city, contributes enormously to a greater appreciation of what the material arts tell us about ourselves and our history. His dedication to learning about the ceramics of British Columbia has infected others and through the acts of collection, and of knowledge-gathering, Lawrence has initiated what we hope will be an amendment in the status and situation of the ceramic and material arts of British Columbia.

Debra Sloan is an artist living in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Written in Clay, Ceramics from the Collection of John David Lawrence is on view between May 25, 2025 and January 4, 2026, at the Vancouver Art Gallery, Vancouver.

Subscribe to Ceramics Now to read similar articles, essays, reviews and critical reflections on contemporary ceramics. Subscriptions enable us to feature a wider range of voices, perspectives, and expertise within the ceramics community.

Captions

- Figure 1 (featured image). John David Lawrence in his home, Photo: Vancouver Art Gallery

- Figure 2. Installation views of Written in Clay: From the John David Lawrence Collection, exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery. Photo: Courtesy of Vancouver Art Gallery

- Figure 3. Installation views of Written in Clay: From the John David Lawrence Collection, exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery. Photo: Courtesy of Vancouver Art Gallery.

- Figure 4. Installation views of Written in Clay: From the John David Lawrence Collection, exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery. Photo: Courtesy of Vancouver Art Gallery

- Figure 5. Axel Ebring, Pitcher, c. 1930s, ceramic, Collection of John David Lawrence, Photo: Courtesy of Vancouver Art Gallery

- Figure 6. Axel Ebring, Flowerpot, c. 1940s, ceramic, Collection of John David Lawrence, Photo: Courtesy of Vancouver Art Gallery

- Figure 7. Laura Wee Láy Láq, Olla, 1992, ceramic, Collection of John David Lawrence, Photo: Courtesy of Vancouver Art Gallery

- Figure 8. Wayne Ngan, Tea Bowls, c. 1970s, ceramic, Collection of John David Lawrence, Photo: Courtesy of Vancouver Art Gallery

- Figure 9. Charmian Johnson, Bowl, c. 1970s, ceramic, Collection of John David Lawrence, Photo: Courtesy of Vancouver Art Gallery

- Figure 10. Installation views of Written in Clay: From the John David Lawrence Collection exhibition, Laura Wee Láy Láq spotlight display. Courtesy of Vancouver Art Gallery

- Figure 11. Installation views of Written in Clay: From the John David Lawrence Collection, exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery. Photo: Courtesy of Vancouver Art Gallery. Debra Sloan, Baby 2014 & Tiny figures,1977, photo: Author

- Figure 12. A sample of roads and travel in BC in the 1920s, Photo courtesy of BC Archival photographs.

Footnotes

- Exhibition curated by Diana Freundl, Interim Director of Collections & Senior Curator, Michael J. Prokopow, Independent Curator, and Stephanie Rebick, Interim Director of Exhibitions & Publishing with Andrea Valentine-Lewis, Curatorial Assistant

- Publication – The Place of Objects, The John David Lawrence Collection, 2025, edited by Stephanie Rebick and Michael J. Prokopow, Vancouver Art Gallery

- Modern in the Making, Post-War Craft and Design of British Columbia, July 18, 2020 – January 3, 2021, Vancouver Art Gallery, curated by Daina Augaitis, Allan Collier, and Stephanie Rebick

- Personal and Material Geographies, September 10 – December 11, 2020, Craft Council of BC, Curated by May-Beth Laviolette, in partnership with the Italian Cultural Centre.