By Beth Williamson

Jupiter+ is an ambitious off-site programme run by Jupiter Artland in Scotland. The brainchild of Jupiter’s co-founder, the sculptor Nicky Wilson, it aims to bring world class art out of the gallery and into high streets across Scotland. Now in its fourth year, the programme has previously run in Perth (2022), Ayr (2023) and Paisley (2024). In the 2025 offering, housed in a disused estate agent in Reform Street at the heart of Dundee, Lindsey Mendick’s new installation Growing Pains: You Couldn’t Pay Me to Go Back catches the eye and interest of passersby young and old. In this former retail unit, reimagined as an immersive multi-sensory artwork, the creative use of public space enables the opening of dialogue and issues an invitation, to young people in particular, to imagine themselves as artists. Crucially, Jupiter+ runs a bespoke learning programme in the high street too, providing opportunities to develop critical thinking, collaboration, creative activism and self-development. Jupiter’s Youth Collective ORBIT runs in conjunction with Jupiter+, bringing together young people for a year-long, youth-led programme that has the potential to transform lives.

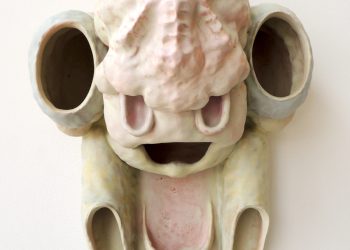

Growing Pains, an idea and installation that Mendick has called “the estate agents from hell”, draws in new audiences and inspires the next generation of creative practitioners. Mendick’s autobiographical work offers a form of working through, asking the viewer to explore their own personal histories, however difficult that may be. In a previous commission for Jupiter Art Land, Mendick installed Sh*tfaced (2023) in Jupiter’s Steadings Gallery where her ceramic tableaux captured the indulgence and aftereffects of binge drinking culture. Other installations on the site at that time – Shame Spiral and I Tried So Hard to Be Good, also dealt with restraint and abandon and the theme of self-destructive tendencies at play. Now in Growing Pains, Mendick revisits her teenage years through ceramics and film. In so doing, she creates a space for today’s teenagers to talk about what is important to them, about their fears and emotions, hopes and dreams.

At first glance, Growing Pains looks like a typical estate agent. One window is completed covered with advertising showing suburban houses rolling down a leafy hill with the London sky scape beneath. Look closer, however, and you will notice the face of a spotty youth, Disembodied teenage mouths filled with brace work and colorful butterfly hairclips float across the vista. In the other window, advertisements for houses for sale hang in three vertical lines, supported by fine metal link chains that echo the aforementioned brace work. Each advert shows a smart middle-class house with the unnerving text beneath it – Growing Pains: You Couldn’t Pay Me to Go Back There. Something is awry here. Inside the office nothing is as you would expect. A series of half a dozen or so ceramic doll’s houses are set atop pedestals so that visitors can walk around and between them. Glazed in murky shades of browns and greens, each house is purposely cracked open and an array of objects burst forth from within, conveying something of the uncontainable pressures that teenagers face in contemporary times. The fashionable training shoes of Mendick’s youth, a mobile phone, hair straighteners, cigarettes, empty bottles of alcohol, computer game consoles, makeup and items of underwear populate these dilapidated houses, turning what could be a house of dreams into a house of nightmares that seems to be on the verge of dereliction. It’s a troubling scene made even more so when you watch the associated film in the adjoining space where Mendick drives around the areas she grew up in, sharing stories with the viewer. There is no question that Medick’s experience of her teenage years was traumatic for all sorts of reasons. It is an incredibly emotional film and one that shares the uniqueness of her experience while, at the same time, showing the common emotional trials all teenagers share.

What took Mendick to art school in the first place is no mystery. She tells me that at secondary school in north London she benefited from forward thinking art teachers and, from the age of 14, never wanted to do anything else. The rise and reputation of the Young British Artists at that time made anything seem possible. With typical honesty, Mendick confesses to feeling alone and ashamed as a teenager. It was discovering the work of Tracey Emin, she says, that saved her. In 1995 Emin made her now-famous work Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–95. The teenage Mendick made Everyone I Have Ever Kissed, and so began an artistic career that has truly reimagined what ceramics can do, and become, as a critical medium for contemporary art.

Working initially with air drying clay, Mendick didn’t fire her first ceramics until she was 27 years old at the Royal College of Art. While nervous about stepping outside her own boundaries of experience, she has never looked back. She is constantly learning and using different clays, pushing herself and it as a medium. “I think I must be addicted to the constant failure of it”, she says laughing. There is, of course, a battery of troubleshooting, glaze testing and such like to attend to in the process of making, but as Mendick explains: “when you’re an artist, very rarely do you have that, voila, like when a baker opens the oven and suddenly you have all these croissants from nothing. As an artist, you see so much of the process, it’s really hard. But then when I open the kiln, and something I’ve made is finished, I’m able to experience it as a viewer. I think I’m just addicted to that rush”.

As for the medium itself, there is no other medium that is so intrinsically hand to heart for Mendick. Her work is deeply emotionally invested. Mendick again: “everything that I experience in the studio is so diaristic. I can go into the studio and create something that’s based on what’s just happened to me that day. As my work is about diary and autobiography, it seems that these ceramic objects are entities, forged from myself. With ceramics, I feel I’m creating something from nothing. When I go into the studio, it’s really meditative and I can just lose myself in it. I think it’s been really important to me because it has slowed me down quite a bit”.

Mendick has been open about her own battles with mental health and I wondered how difficult it might be to work things though in clay and then reveal them to the world, particularly in Growing Pains which deals with such a vulnerable and difficult stage of life. Mendick shares that she has grown up unable to shake off much of that teenage pain.

“I’ve been waiting probably 10 years to make this show and thinking there’ll be a right time when it doesn’t prick my eyes, talking about some of the things that happen. But then I realised that it was more important to talk about a subject that still feels so raw”. The unresolved nature of Mendick’s teenage troubles prompts us to discuss how some things never leave us. It is with her typical generosity that Mendick explains how, for her, the work connects to these difficult emotions. “One of the reasons it’s so great with Jupiter+ is that this isn’t just a show, it’s a springboard and that’s what I believe art should be. I want the works to be conversational, conversation pieces about difficult things that we have to say to each other. I make like no one’s watching, but I needed something like Jupiter+ to be able to take on the complexity of it as a story”.

The technical challenges of working with clay in this way are considerable. Making the houses in Growing Pains was most challenging of all. A team of people had to carry them to the kiln. Mendick always liked the idea of them cracking, playing with the idea of bursting out the scene, if you like. “I was thinking about how teenagers punctuate everything. You create a life, and then you cannot control them. I think that was what was what was happening with my parents. I think quite often, we go through all of that and we think, but if I had kids, I could do it better. But you can’t, you can’t control it”. There is a sense of that lack of control with ceramics and with Mendick too as she points out “I do think you have to collaborate with your kiln”. That said, there is nothing organic or intuitive about Mendick’s process. Ceramic may be the protagonist with the show built around it, as Mendick puts it, but she is always thinking and planning what is next in the process. She has created an enormously raw, honest and generous artwork here. What is next for Growing Pains depends upon the young people of Dundee.

Beth Williamson is an art historian and writer specialising in modern and contemporary art in Britain, with a particular interest in art education, craft, and ceramics. A former Research Fellow at Tate, she co-curated the exhibition Basic Design at Tate Britain in 2013 and has written widely on British art and pedagogy. Her essays and reviews on art, craft and ceramics have appeared in publications such as The Art Newspaper, Sculpture magazine, Studio International, and Ceramic Review.

Lindsey Mendick – Growing Pains: You Couldn’t Pay Me to Go Back is on view at Jupiter+ (Part of Jupiter Artland), Dundee, between September 12 and December 21, 2025.

Subscribe to Ceramics Now to read similar articles, essays, reviews and critical reflections on contemporary ceramics. Subscriptions enable us to feature a wider range of voices, perspectives, and expertise within the ceramics community.

Captions

- Lindsey Mendick, Growing Pains, 2025. Courtesy of the artist and JUPITER+, Dundee. Photography by Ruth Clark, except otherwise noted