Michelle Solorzano is a figurative ceramic sculptor whose work explores themes of immigration, identity, and culture, interweaving personal narrative with broader historical and ancestral influences. Originally from Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, she moved to New York with her family at the age of fifteen. Her art practice is deeply rooted in the complexities of bicultural identity and the layered legacies of colonization, shaped by Dominican heritage—Taíno, African, and Spanish.

Solorzano holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Painting and Ceramics from the State University of New York at Potsdam and a Master of Fine Arts in Ceramics from Indiana University’s Eskenazi School of Art, Architecture + Design. Though she has been making art since childhood—using discarded materials, paper mâché, and drawing to bring her ideas to life—it wasn’t until her second year of undergraduate studies that she touched clay for the first time. That first ceramics course prompted her to switch majors from Art Education to Fine Arts, solidifying her commitment to ceramics. She was immediately drawn to the malleability, versatility, and forgiving nature of clay, which remains central to her sculptural practice.

Now based in California, Solorzano is a long-term Artist in Residence at the American Museum of Ceramic Art (AMOCA), where she also shares her passion for ceramics through teaching. Her work has been recognized nationally, most recently as a 2025 NCECA Emerging Artist and a recipient of the Helen Zucker Seeman Writing and Research Fellowship for Women. She was named a 2024 Ceramics Monthly Emerging Artist, and has also received the Bloomington Arts Commission Emerging Artist Grant, the Christyl Ann Boger Memorial Award, and the Nelda Christ Memorial Award.

Visit Michelle Solorzano’s website and Instagram page.

Featured work

Selected works, 2022-2025

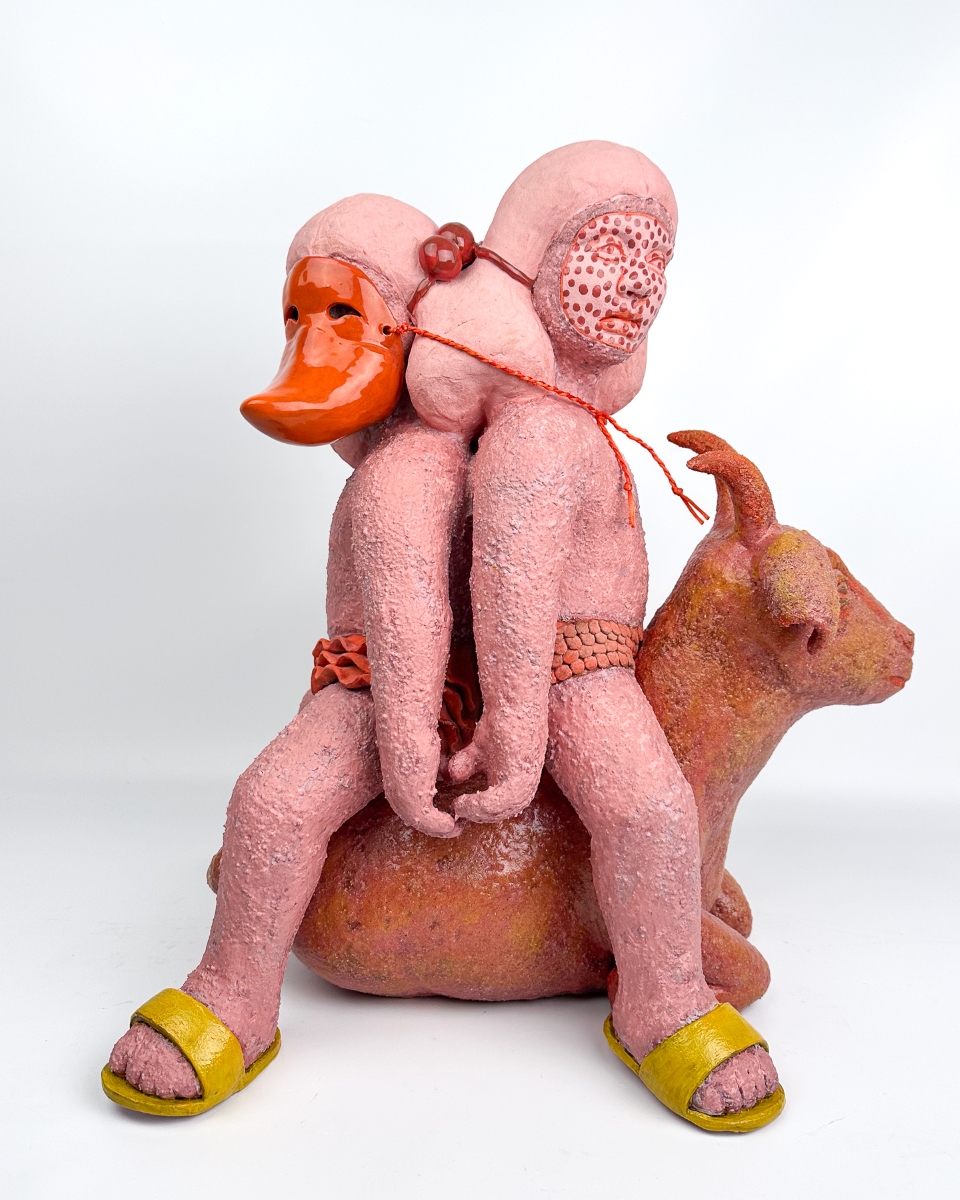

My work is a personal exploration of cultural identity, deeply shaped by colonization, immigration, and assimilation. Central to this exploration is the Dominican Carnaval, a vibrant tradition that merges performance, satire, and resistance. While widely celebrated for its colorful costumes and energetic parades, Carnaval also serves as a platform for confronting social hierarchies, challenging colonial legacies, and expressing protest through humor and inversion. Through extensive research, I aim to rediscover the historical and cultural significance of these traditions, highlighting the lasting impact of colonization on contemporary Dominican society.

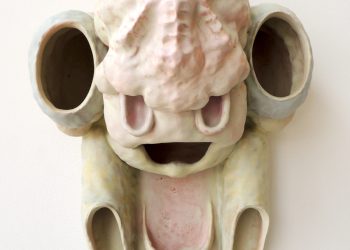

I create figurative ceramic sculptures that incorporate mixed media and found objects, often working in various scales to evoke either confrontation or vulnerability. My forms are primarily built using slabs, allowing me to create surfaces that resemble skin: pliable, raw, and capable of holding tension. These techniques help me layer narrative and meaning, visually conveying themes of identity, memory, and resistance.

Growing up in the Dominican Republic, I was taught a colonized version of my country’s history. A version that prioritized European narratives while erasing or distorting its Indigenous and African roots. Migrating to the United States added another layer to my identity, prompting a deeper inquiry into the overlooked, forgotten, or misrepresented aspects of Dominican culture. My work seeks to deconstruct these colonial narratives and reclaim a more authentic sense of identity acknowledging the fusion of Taíno, African, and Spanish influences.

Symbolism and surreal narratives run throughout my practice, reflecting challenges I’ve faced as an immigrant: language barriers, cultural displacement, prejudice, and the complexities of assimilation. Themes of duality and biculturalism express the constant negotiation between American and Dominican identities. By embedding myself into these narratives, I aim to foster a deeper connection with the viewer and offer a more humanized representation of the immigrant experience.

Carnaval’s rebellious spirit is echoed in my work through color, surreal elements, movement, masks, and layered storytelling. Color plays a vital role, drawing viewers in visually while conceptually guiding them toward difficult conversations around social and cultural transformation. The fantastical nature of Carnaval, often referred to as the “world upside down,” provides a temporary space where power structures are inverted. The satirical “devil” takes center stage in a society heavily influenced by the Catholic Church and government. This character becomes a tool to question, mock, and subvert authority. In this temporary freedom, the community explores dynamics between religion, politics, and identity.

Two devil figures appear frequently in my sculptures: Los Platanuses and Lechón Pepinero. Los Platanuses wear masks made of gourds and body suits adorned with dried plantain leaves, symbolizing both resistance and survival. They honor the legacy of enslaved Africans and critique the abuses of plantation owners and the trauma of Trujillo’s dictatorship. Lechón Pepinero, my personal favorite, features a stylized mask with pig-like eyes, ears, and a duck’s bill as an exaggerated, whimsical distortion rooted in folklore and satire.

In addition to Carnaval, my most recent body of work is inspired by La Niña de la Espina (The Girl with a Splinter), a painting I saw in many Dominican households growing up. It depicts a young girl calmly picking at her foot, radiating a sense of innocence and stillness. That image held a quiet, nostalgic power for me. One that resurfaced years later and sparked a deeper curiosity about its origins and widespread cultural presence.

Through research, I learned that La Niña is not unique to the Dominican Republic but beloved across Latin America. Some believe the image originated from a set of European stamps circulated in the region, while others trace it to a lithograph inspired by Spinario, a Hellenistic sculpture of a boy removing a splinter. In some countries, like Costa Rica, she is known as La Nigüenta, often kept as a three-dimensional figure in homes and even venerated as a saint.

These discoveries led me to reimagine La Niña through my own lens. I began a series of sculptures that take her out of her original context and place her into new scenarios informed by Caribbean aesthetics, personal memory, and the social and political realities I navigate. In this series, La Niña becomes a vessel for layered storytelling bridging the nostalgic and the contemporary, the familiar and the transformative.

By referencing naïve aesthetics, embracing Caribbean vibrancy, and incorporating Taíno symbology, I challenge colonial hierarchies of value and beauty in art. My practice is a reclamation of history, identity, and voice. Through sculpture, I aim to contribute to a more inclusive and expansive visual language that centers marginalized stories, honors cultural hybridity, and opens space for imagining new narratives.