By Vince Montague

The late filmmaker Yasujiro Ozu (1903-1963) became known in cinematography for his “tatami shot”, a camera angle that places the optical lens much lower to the ground. In Western cinema, the camera is usually placed at shoulder height. Ozu’s pioneering perspective placed the camera at knee-height, the same perspective as if sitting on a floor. The viewer is not above the work, but is equal to or just below it, developing a more intimate visual relationship with the subject.

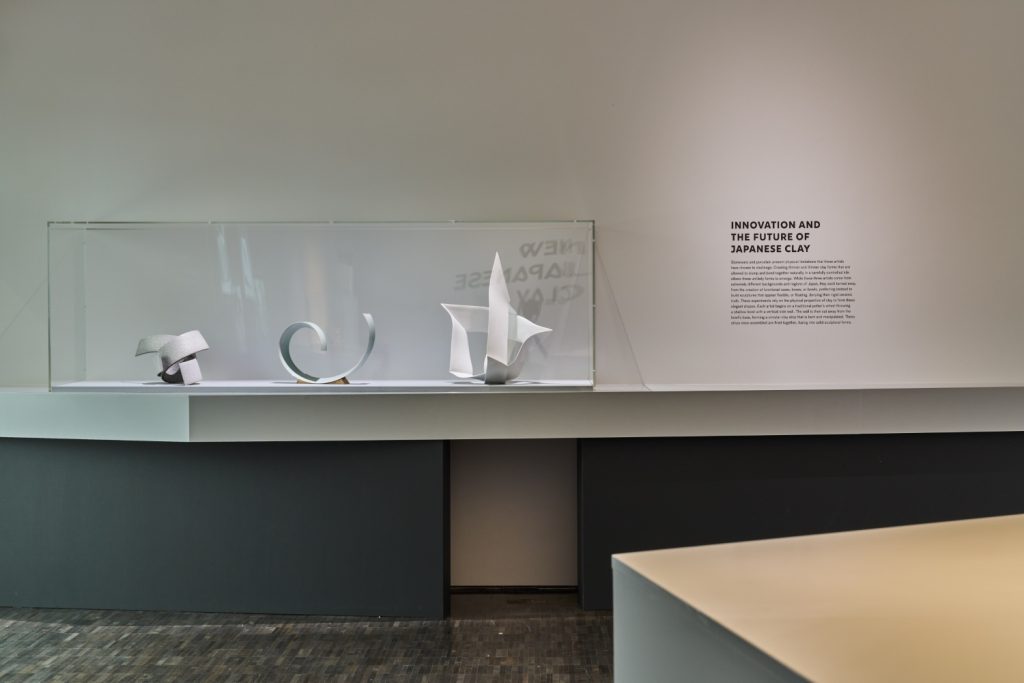

The change in perspective is key to understanding the exhibition, New Japanese Clay, at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco (through February 2026). The long, dark exhibition room employs a waist-high platform that stretches the length of the space, spotlighting nearly thirty vessels from contemporary Japanese ceramicists. The viewer walks the length of the tall winding countertop, taking in each vessel in a manner that makes each artwork in this show feel monumental yet accessible.

New Japanese Clay represents highlights from the collection of Dr. Phyllis A. Kempner and Dr. David D. Stein. The exhibition is framed by the presence of Minghei pots that open the gallery show. There are only a few, like for example a “Bamboo-shaped Vase” (approximately 1925-1950) by Kitaoji Rosanjin, and of course “Oval Vase” (1970) by Shoji Hamada. These quiet pots cast a deep shadow over the exhibition, as the weight of centuries of craft and the discipline of making unobtrusive functional pottery can’t be easily ignored.

Stepping away from those Minghei pots, one instantly feels the change in perspective approaching the work by these contemporary artists; each of these ceramicists have mostly broken free from the constraints of function into individual and expressive works using a variety of methods and processes to achieve their visions. Rather than seeing this work from the traditional viewpoint of the influence of Minghei, I wondered if I encountered these works in a different context, from a different perspective, how would I respond? What is it beyond the echo of Minghei that these artists and these works have in common? Are there qualities in this collection of contemporary artists that separates them now from other cultures? The internet and the advances in communication and sharing of ceramic information in the last thirty years has created a wide sphere of influence. And although the Minghei tradition might be in the background, there are other signs of cultural influence and artistic independence.

In all of the vessels of New Japanese Clay, each work itself feels like a tour de force of technique, discipline, and tenacity. Standing out are two pieces by Yukiya Izumita, whose two works feel like a master class in patience and technique. His free-standing geometric shapes initially remind one of origami, but they also read like cross-sections of exposed earth, his organic vessels possessing both the discipline of craft and the randomness of fire and clay. In particular, “Aurora No. 4” from 2012 reflects a deeper wisdom that comes from the contradictory lightness of the interlocking forms and the density of the fired clay.

Nagae Shigekazu’s “Forms that Entwine” (2017) is proof of his dexterity as a craftsman, but also his conceptual thinking about porcelain slip-casting. Like Yukiya, Shigekazu works with free standing origami-inspired shapes where the viewer is left wondering how the artist manipulated the paper-thin clay into shapes that seemingly betray gravity. In the end, the ribbon-like form surprises and almost transforms itself into an abstract figure. The poetry in this work lives in the lightness of the porcelain and the arching shapes that display both strength and fragility.

Even though Mihara Ken trained for one year under Minghei potter, Kenji Funaki, he soon followed his own career. His piece, “Mindscape,” intrigues because of the shaping of the interior space, the dark and mysterious center from which the sculpture begins. There’s a soulful quality here in the rusty colors that reminds one of the abstract sculptures of Richard Serra, undulating forms that spiral in the imagination. The clay appears to be pushed to the brink on the unglazed surface, but the underlying foundation feels smooth and flows almost like water. Inside this piece of modern minimalism lives a work that resonates within a landscape of silence and meditative self-reflection.

Inaba Chikako makes vessels that appear organic, but there is something edgy and contemporary about her, “Leaf-shaped vessel” (2020). The glow coming from the piece comes from the powder-like porcelain carved into the shape of an unfolding leaf. The gesture is literal, but the feeling in the presence of the work feels hesitant, unsure, and almost shy. The moment captured in the unfurling is the process towards opening, that awkward stage that transfers the tenuousness of being vulnerable into the fully outstretched gesture of living. Like many of the pieces in the exhibition, there is a deep introversion in the work, a place where the intensity of the artist becomes the potency of the piece.

While glancing at a slideshow of images of Shoji Hamada and Bernard Leach, I came upon the work of Katsumata Chieko. Her vessels are referred to as “biomorphic” and her work, “Akoda Gourd” (2014) pulses with energy and vitality. This gourd is a common form familiar to many cultures, but here the gourd does not feel like a shell. Rather, the gourd has a modern sensibility, but like Chikako’s “Leaf-Shaped Vessel” this piece has movement, almost as if it is going to spring up into the air. The coloring and the texture draws the viewer towards the center, looking down into its depth almost as if staring into a darkened pond. Although beautiful, the work also feels quietly radical.

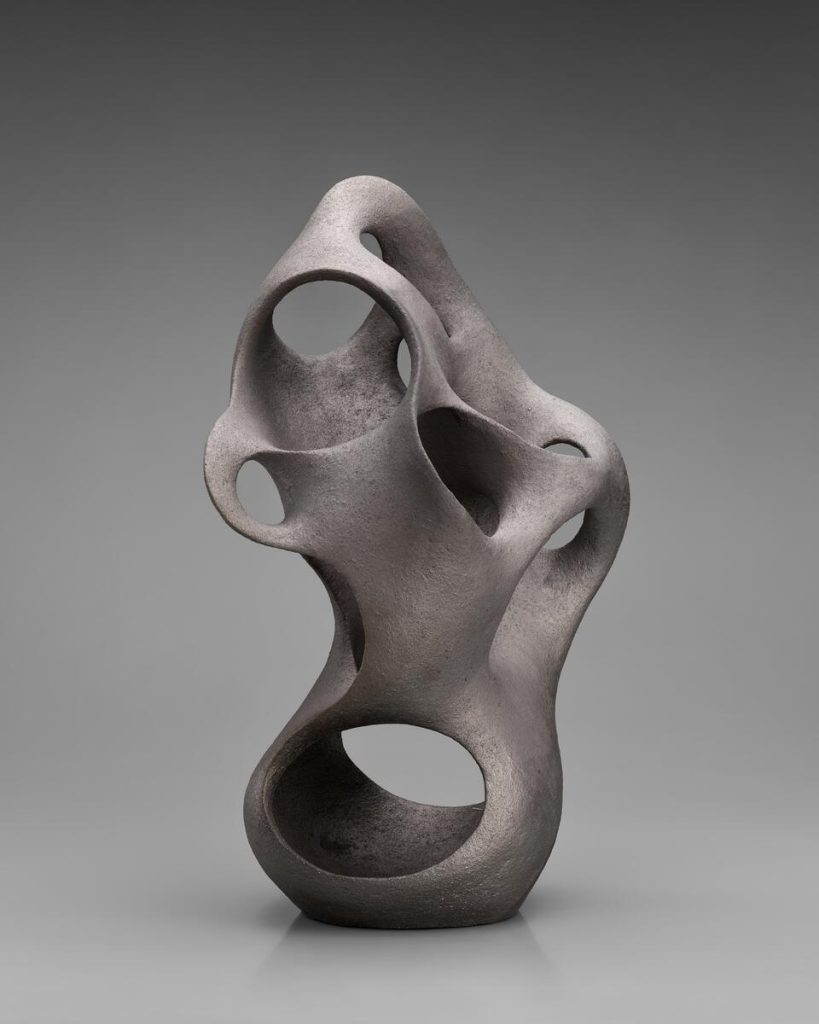

The most dynamic piece in the exhibition is Toru Kurokawa’s “Protocell G” (2017), a slinky, elegant helix form that billows upward like reeds floating in a darkened sea. The title indicates an experiment of some sorts, an intention to discover, an inquiry into new beginnings, a marriage between science and art. Looking at the piece and following the lines as they extend upwards, I felt as if a dilemma had been resolved, at least within the work itself. There’s a live-action feeling to this sculpture that stands out as potentially pushing back on the shadow of Minghei. I felt as if I were watching this work by Kurokawa come alive, the shapes transforming into musical notations, where the artist is both the composer of the music and the player of the song.

At the end of the exhibition, however, I was lured back again to Suzuki Goro’s “Yashichida-style Lidded Box” (2014) a contemporary version of an Oribe-style box. This contemporary take on Oribe exhibits warm colors while the rough cuts contrast with the stylish surface marks. Like many others, I have a hard time resisting these Oribe pots and the warmth they exude. To work in ceramics in Japan is to carry alongside a deep history of craft and beauty that is hard to ignore. However, I think it’s also important that we change perspective and see these new ceramic artists in their own right. The history of ceramics is rich and plentiful and should be a resource for contemporary ceramics, not just a framework for viewing.

Vince Montague is a ceramicist and the author of Cracked Pot, a memoir about clay and grief.

New Japanese Clay is on view at The Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, California, through February 2, 2026.

Subscribe to Ceramics Now to read similar articles, essays, reviews and critical reflections on contemporary ceramics. Subscriptions help us feature a wider range of voices, perspectives, and expertise in the ceramics community.

Captions

- Installation views of New Japanese Clay at the Asian Art Museum, August 15, 2025 – February 2, 2026. Photographs © Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, by Kevin Candland

- Bamboo-shaped vase, approx. 1925-1950. by Kitaoji Rosanjin (Japanese, 1883 – 1959). Stoneware with glaze. Asian Art Museum, Gift of Dr. Phyllis A. Kempner and Dr. David D. Stein. Photograph © Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

- Oval vase, 1970. by Hamada Shoji (Japanese, 1894 – 1978). Stoneware with glaze. Asian Art Museum, Gift of Dr. Phyllis A. Kempner and Dr. David D. Stein. Photograph © Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

- Aurora No. 4, 2012. by Izumita Yukiya (Japanese, b. 1966). Stoneware. Asian Art Museum, Promised gift of Dr. Phyllis A. Kempner and Dr. David D. Stein. Photograph © Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

- Forms that Entwine, 2017. by Nagae Shigekazu (Japanese, b. 1953). Porcelain with glaze. Asian Art Museum, Gift of Dr. Phyllis A. Kempner and Dr. David D. Stein. Photograph © Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

- Protocell G, 2017. by Kurokawa Toru (Japanese, b. 1984). Smoke-infused, unglazed stoneware. Asian Art Museum, Gift of Dr. Phyllis A. Kempner and Dr. David D. Stein. Photograph © Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

- Leaf-shaped vessel, 2020. by Inaba Chikako (Japanese, b. 1974). Stoneware with glaze. Asian Art Museum, Gift of Dr. Phyllis A. Kempner and Dr. David D. Stein. Photograph © Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

- Akoda Gourd, 2014. by Katsumata Chieko (Japanese, b. 1950). Stoneware with colored slip. Asian Art Museum, Promised gift of Dr. Phyllis A. Kempner and Dr. David D. Stein. Photograph © Asian Art Museum of San Francisco